On the morning of March 20, 1998, an F3 tornado ripped through Hall and White Counties, leaving destruction and tragedy in its wake.

It was a day like any other as parents prepped their kids for school and people drove to work. All of that changed at a moment’s notice when a tornado cut its way across Hall and White Counties, leaving 13 dead and 171 wounded. Schools, workplaces and homes were completely destroyed as many residents of Northeast Georiga were forced to pick up the pieces of their shattered lives.

At 6:30 a.m., police scanners erupted saying an officer was down after being hit by a car. Dawson County Sheriff’s Deputy Bobbie Hoenie was directing traffic around fallen debris and other weather-related accidents when she was struck and killed, becoming the first victim of the storm.

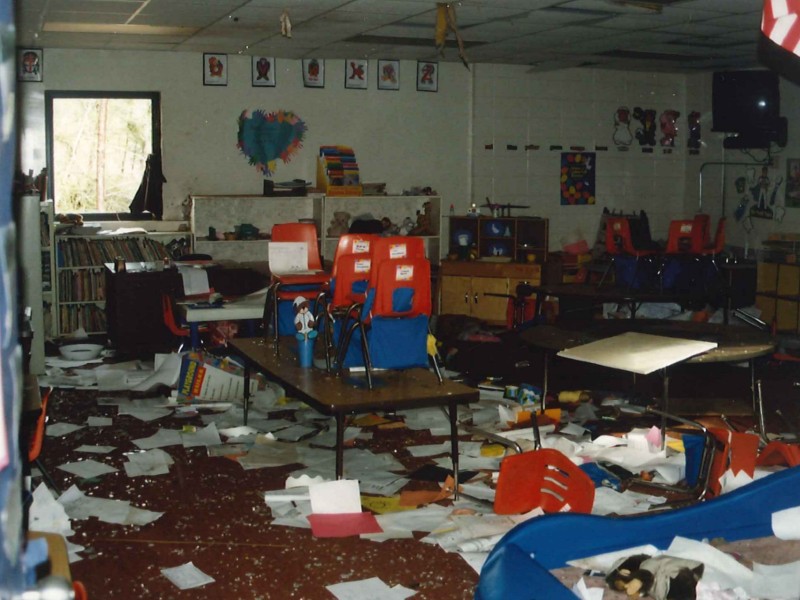

As the tornado gorged its way through Hall County, it damaged Lanier Elementary before killing a deliveryman on the school grounds. Portions of the elementary school were left destroyed beyond repair. The tornado then moved toward North Hall High School, where it ripped the roof off.

The destruction was fast and aggressive, as the twister touched down at approximately 6:25 a.m. and began dissipating around 6:40 a.m. 40 homes were completely decimated and 130 were damaged. 45 mobile homes were reportedly destroyed or damaged as well, some of which were lifted, thrown and crushed. A large portion of the fatalities were residents in mobile homes.

Animals were not spared either, as nearly 100,000 chickens and 40 cattle were killed. The estimated damages from the 1998 tornado range from $15 to $20 million.

On the 25th anniversary, AccessWDUN honors those who were impacted by this tragedy, shedding light on their experience of standing in the path of destruction.

‘Picked up and slammed down into a pond’; The First Responders

Captain Joe Carter with the Hall County Sheriff’s Office was one of the first responders on the morning of the tornado. He said prior to the destruction, there was hardly any bad weather as the twister didn’t show up on any radars.

“I was the only supervisor working,” Carter said. “I had just left a car fire on the Interstate between exit four and exit eight. It wasn’t even raining — bad weather never entered our minds. It was toward the end of the shift. We got off at seven in the morning. And a call comes out about a possible tornado that hit down around North Hall.”

Carter said on his way to North Hall, he noticed several downed trees, commenting on how that was common during big storms in Georgia. Once he turned onto Mount Vernon Road, he saw downed telephone poles and started realizing this was bigger than he thought.

“It was terrible,” Carter said. “It just looked like — I don't know, I've never seen a big bomb go off, but it was just mass destruction. It was just piles of rubble where I knew either houses or mobile homes had been. They were just gone. There were obviously some seriously injured people laying on the side of the road, walking down the road. That’s what I pulled up on.”

Once Carter was on the scene, he said there were numerous people with severe injuries, many of which were naked from the intense and brutal winds of the tornado. The fire and police departments immediately began administering aid, giving out blankets and searching for people.

Carter then directed responders to begin assembling injured persons in the gym of the school in order to set up a triage area for EMTs. At this point in the day, Carter and many of his officers had been working for almost 18 hours straight, since the tornado swooped in at the end of their shift.

“Everybody was still in a little bit of shock when I first arrived, because, I mean, there were some people literally crawling out from under the rubble when I got there,” Carter said. “By the time I got to North Hall, there was no rain.”

After Carter assessed the magnitude of the tornado, he spoke with his supervisor, asking him to send all the units they could muster.

“Find a way to get people up here, we‘re going to need all the help we can get,” Carter said. “I asked dispatch to put out a call for mutual aid for all the surrounding counties, and really good response from agencies even down around Metro Atlanta. Before I let off, there were probably 75 officers from other agencies.”

Carter said they separated civilians who were there to help, EMTs and other officers into groups, informing them to leave dead bodies where they were so deputies could ID them and investigate further.

“You don't understand the power of a tornado until you see something like that,” Carter said.

Lieutenant Kiley Sargent with Hall County was another officer who was on the scene the morning of the tornado.

“I remember vividly,” Sargent said. “The sirens and the number of emergency vehicles going to Lanier Elementary and North Hall High School … I specifically remember being assigned to, I believe it was Clermont Highway, it was a double-wide mobile home that had literally just gotten picked up and slammed down into a pond.”

A 12-year-old girl and her grandfather were in the mobile home when it was lifted and cast into the nearby pond. They both died in the accident. Sargent noted that initially, they couldn’t find the grandfather, later discovering his body stuck under debris in the pond.

“Everything was a crime scene, the whole county was a crime scene,” Sargent said. “People that weren't affected were coming out and helping others that were affected … I was like a young officer and I've never seen anything like that. I've never been part of anything — I've seen wrecks and single incidents and stuff, but nothing of that magnitude, nothing of that magnitude.”

‘Do we have a school?’; North Hall Student Reacts

Riverbend Elementary School Principal Keri Smith was a 17-year-old junior at North Hall High School at the time of the tornado. She said she remembers waking up to her mom telling her she wouldn’t be going to school that day.

“I remember us kind of coming together about mid-morning and wanting to go help,” Smith said. “And so we bought some bottled waters and thought we were going to get to go and help others and really quickly realized just how bad it was. I remember driving down Thompson Bridge Road and getting almost to Mount Vernon Road, and traffic was stopped and turned around. And I think that's when it hit us that this was pretty serious and that the weather really took down a lot of the area.”

Not having cell phones complicated matters further, as Smith was unable to find out which of her friends were impacted or where help was specifically needed. Smith said she resorted to leaving messages with people.

“The relief when some of my closest friends were able to call our home phone and tell us that they were okay,” Smith said. “And then of course in the days after that, just waiting to find out — do we have a school, are we going to school?”

The tornado crashed through Hall and White Counties roughly one week before spring break, forcing North Hall High to shutter its doors for two full weeks. Smith noted that under different circumstances, many kids would have been happy to be off school for a longer period of time — but this extended break came with a cost.

“North Hall has always been just a small hometown community,” Smith said. “And I grew up in that area and went to school at Riverbend Elementary and then went to North Hall Middle and North Hall High, and I do remember just the community coming together. Everybody helping one another.”

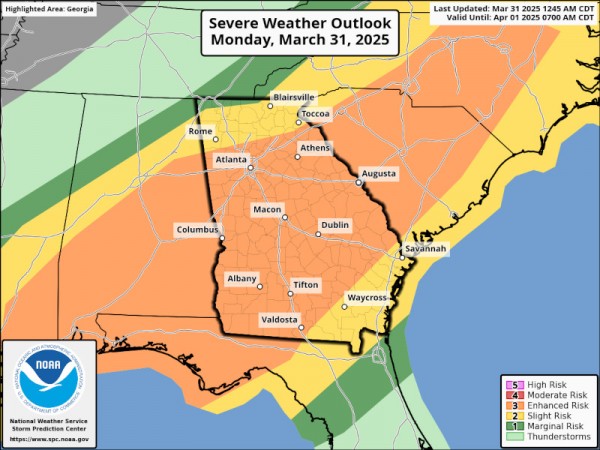

As the current principal of Riverbend Elementary, Smith said preparing for natural disasters in today’s world is critical.

“We keep safety at the forefront of what we do and with weather radios, watching the weather, our district does a great job,” Smith said. “If the weather looks like it's bad, we get to make that decision of whether or not we roll buses. We do practice drills, safety drills with kids all the time. And just raising that awareness — we don't like to scare kids, but we want them to know that if bad weather comes, we know what to do.”

Five years after the deadly tornado, Hall County installed a county-wide siren system that warns of incoming disastrous weather. In tandem with that system, the county now also makes use of a weather transmitter on Wauka Mountain at the Hall/White County line that plugs a weather radar gap in Northeast Georgia.

‘What I learned about our community’; From Local to Global

At the time of the 1998 twister, Kate Maine was serving as the Public Relations Officer for the Hall County Board of Commissioners. She quickly became the primary point of contact for reporters and citizens alike during and after the destruction.

“It was one of the most traumatic and challenging experiences of my career and something that I do reflect on often, because of the lessons that I've learned, but also what I learned about our community,” Maine said.

Maine was preparing for a public affairs television interview that morning when she got a call from Hall County officials requesting her on scene at North Hall High. It was at that point her plans completely shifted.

“When I got there — the tornado actually touched down at about 6:30 a.m. that morning, and I got there probably about 7:15 a.m., 7:30 a.m.,” Maine said. “And of course, there were lots of roads blocked because of the tornado damage, trees down, power lines down, that sort of thing.”

Maine explained how her mother and stepfather lived a mile-and-a-half away from North Hall High, but due to the fallen phone lines, she was unable to get in touch with them to confirm their safety.

North Hall High became the emergency management site, as news crews, responders, police and other community members began pouring in. In coordination with other officials, Maine established site parameters and conducted periodic news conferences. As the days went on, news crews from all over the country and even abroad were there covering the storm’s destruction.

Maine was eventually able to connect with her parents, who managed to get through the twister unscathed. For the next several weeks, she focused on recovery, which was made easier through strong relationships with neighboring counties and businesses.

“It helps to have very close working relationships with colleagues in similar roles across jurisdictional lines,” Maine said. “And I think that was certainly the case with our emergency management officials, and the fire departments and sheriffs because it involves all of those agencies. And then also, of course, other agencies, like the Board of Commissioners.”

Once federal representatives toured the area and assessed the damage weeks later, Maine noted that the county’s recovery efforts shifted into long-term planning.

‘Just wanted to stay there and help’; The American Red Cross Responds

National Headquarters Lead with the American Red Cross Matthew Akins was joined on scene after the tornado by several other Red Cross members, all of whom helped clothe, shelter and feed those in need.

“It was just so much damage,” Akins said. “People staring, dazed, didn't know what was going on, still looking for loved ones. So the first couple of days was trying to feed and trying to shelter, helping people. It was a tough time. And there's only two of us left in the Red Cross that was there that day — myself and Joe Brown.”

Akins mentioned that he and Brown went before the Unmet Needs Committee in the aftermath of the tornado and presented cases of impacted residents who needed funding to cover damages.

“An older man had a chicken house, that was his business, but he did not have insurance,” Akins said. “And he was denied from an SBA loan and all that. So I took his case, me and Mr. Brown did, and we went around the room after presenting and when we got done with the last organization, that man had a new barn and a new chicken house. It was paid for that day.”

Akins and Brown attended the 20th-anniversary remembrance event in Clermont in 2018.

“We went to the memorial, where it's got all the names,” Akins said. “And this one lady, she came up and she remembered me and Mr. Brown. And she had lost two loved ones that day during the tornado. And she wanted to thank us. And so somebody who could remember us 20 years later, really touched my heart.”

The American Red Cross also conducted blood drives in the wake of the disaster. With so many injured, the Red Cross set up blood banks and mobile donation centers. In the fray of the cleanup and immediate aftermath, Akins said it was hard to find time to rest.

“I didn't get to sleep for about four or five days straight,” Akins said. “Even when we had our downtime to try to get rest. It was just the pictures in my head. You couldn't go to sleep. There are still people that need help and you would want to get back out there. You didn't want to take time to eat lunch, you didn't want to go home, you just wanted to stay there and help.”

Akins mentioned that being on scene often seemed surreal — as if time had stopped altogether and the air was still. Having responded to nearly 50 major natural disasters, Akins said the 1998 tornado felt different.

“This one really hit home, it was a different one,” Akins said. “It was in my backyard, I probably live 20 minutes from there. And it was just a hard day.”

For many who were present that day, and as well for those who watched on, the 1998 tornado lives fresh in their minds. Now, 25 years on, it still resides as a moment when the forces of nature battled against the communities of Hall and White County.

It is with great respect that we dig up some of these hard-to-tell stories, honoring the fighting spirit of a people who stand together and grow stronger in the face of despair.

Read about the 10-year Tornado Anniversary in 2008 by clicking here.

Read about the 20-year Tornado Anniversary in 2018 by clicking here.

(A number of current and former AccessWDUN employees contributed to this story through interviews and archived material, including Joy Holmes, Lawson Smith, Rob Moore and Ken Stanford.)