After a few frightening incidents seeing family and friends collapse in Phoenix's grueling heat, Ashton Dolce, 17, began to wonder why his country's leaders were not doing more to keep people safe from climate change.

“I was just dumbfounded," Dolce said.

He became active in his hometown, organizing rallies and petitions to raise awareness about extreme heat and calling for the Federal Emergency Management Agency to make such conditions eligible for major disaster declarations.

Just before his senior year of high school in 2024, Dolce got the chance to really make his concerns heard: He became one of 15 students across the United States selected to join the FEMA Youth Preparedness Council, a 13-year-old program for young people to learn about and become ambassadors for disaster preparedness.

“It was this really cool opportunity to get involved with FEMA and to actually have a specified seat at the table where we could develop resources by and for youth,” Dolce said.

Then came signs of trouble.

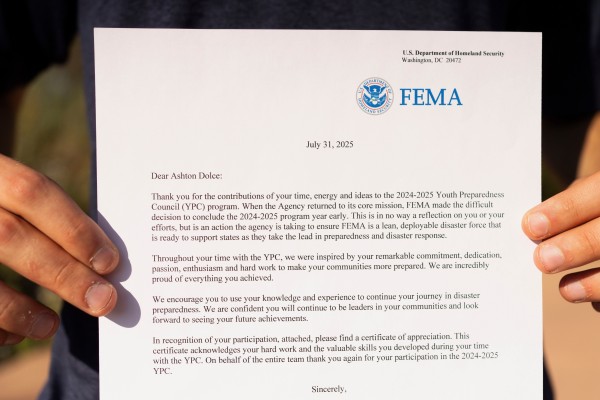

On Jan. 16, the young people were told by email that a culminating summit in the nation's capital this summer was canceled. By February, the students stopped hearing from their advisers. Meetings ceased. After months of silence, the students got an email Aug. 1 saying the program would be terminated early.

“We were putting so much time and effort into this space," he said, "and now it’s fully gutted.”

In an email to students reviewed by The Associated Press, the agency said the move was intended "to ensure FEMA is a lean, deployable disaster force that is ready to support states as they take the lead in preparedness and disaster response.”

The council’s dissolution, though dwarfed in size by other cuts, reflects the fallout from the chaotic changes at the agency charged with managing the federal response to disasters. Since the start of Republican President Donald Trump's second term, his administration has reduced FEMA staff by thousands, delayed crucial emergency trainings, discontinued certain survivor outreach efforts and canceled programs worth billions of dollars.

Dolce said ignoring students undermines resilience, too.

“This field needs young people and we are pushing young people out,” he said. "The administration is basically just giving young people the middle finger on climate change.”

Larger federal programs related to youth and climate are also in turmoil.

In April, the administration slashed funding to AmeriCorps, the 30-year-old federal agency for volunteer service. As a result, 2,000 members of the National Civilian Community Corps, who commonly aid in disaster recovery, left their program early.

FEMA did not respond to questions about why it shut down the youth council. In an email bulletin last week, the agency said it would not recruit “until further notice.”

The council was created for students in grades 8 to 11 to “bring together young leaders who are interested in supporting disaster preparedness and making a difference in their communities,” according to FEMA's website.

Disinvesting in youth training could undermine efforts to prepare and respond to more frequent and severe climate disasters, said Chris Reynolds, a retired lieutenant colonel and emergency preparedness liaison officer in the U.S. Air Force.

“It’s a missed opportunity for the talent pipeline,” said Reynolds, now vice president and dean of academic outreach at American Public University System. “I’m 45-plus years as an emergency manager in my field. Where’s that next cadre going to come from?”

The administration’s goal of diminishing the federal role in disaster response and putting more responsibility on states to handle disaster response and recovery could mean local communities need even more expertise in emergency management.

“You eliminate the participation of not just your next generation of emergency managers, but your next generation of community leaders, which I think is just a terrible mistake,” said Monica Sanders, professor in Georgetown University’s Emergency and Disaster Management Program and its Law Center.

Sanders said young people had as much knowledge to share with FEMA as the agency did with them.

“In a lot of cultures, young people do the preparedness work, the organizing of mutual aid, online campaigning, reuniting and finding people in ways that traditional emergency management just isn’t able to do,” she said. “For FEMA to lose access to that knowledge base is just really unfortunate.”

Sughan Sriganesh, a rising high school senior from Syosset, New York, said he joined the council to further his work on resilience and climate literacy in schools.

“I thought it was a way that I could amplify the issues that I was passionate about," he said.

Sriganesh said he got a lot out of the program while it lasted. He and Dolce were in the same small group working on a community project to disseminate preparedness resources to farmers. They created a pamphlet with information on what to do before and after a disaster.

Even after FEMA staff stopped reaching out, Sriganesh and some of his peers kept meeting. They decided to finish the project and are seeking ways to distribute their pamphlet themselves.

“It’s a testament to why we were chosen in the first place as youth preparedness members," Sriganesh said. "We were able to adapt and be resilient no matter what was going on.”