CHARLESTON, W.Va. (AP) — After surviving teen homelessness and domestic violence in West Virginia, 23-year-old Ireland Daugherty was finally feeling stable: She had her own apartment, a job and was studying for a four-year degree.

Ashley Cain, 36, was celebrating four years of sobriety and working with a nonprofit that trains workers to remediate long-abandoned factories and coal mines into sites for manufacturing and solar projects.

Federally funded programs provided both women with a social safety net and employment in one of the nation’s poorest states, where nonprofits play a vital role in providing basic services like health care, education and economic development.

“We are a state that heavily, heavily relies on government funding,” said Daugherty, who works for an organization that helps young adults transitioning out of the foster care system. “And I know that’s not something that everyone wants to hear, but it’s the reality.”

Two weeks ago, the White House froze spending on federal loans and grants, plunging organizations across the country into uncertainty and creating chaos for nonprofits in the poorest, most rural states, like West Virginia. President Donald Trump's administration rescinded the order, but a federal appeals court found Tuesday that not all federal funding had been restored.

West Virginia's reliance on federal funds to help address deeply ingrained issues makes it particularly vulnerable to the new administration's sweeping actions in a state where Trump support has run deep since his first presidency. In three elections, he has won every county.

West Virginia has the nation's highest rate of opioid overdose deaths, kids in foster care, obesity and diabetes and 1 in 4 children lives in poverty. The state also has widespread infrastructure issues, from polluted drinking water to patchy broadband, and was expected to benefit heavily from federal spending packages focused on revitalizing communities.

The organization Cain works for, Coalfield Development, helped leverage almost $700 million for projects tied to Biden administration spending packages, funding 1,000 jobs in West Virginia alone. It supported similar federally funded projects cleaning up abandoned mine sites and setting up solar arrays in Kentucky and Pennsylvania.

Part of the nonprofit's role is to recruit and train the local workforce for projects, which is personal for CEO Jacob Hannah, who comes from three generations of coal miners and saw his father laid off from the mines.

Those projects, funded by a mix of federal agencies, are now on pause indefinitely. Hannah said his organization received communications that their awards are “under review” with limited details.

“It's been a lot of, how do we figure out how to keep doing our work and not just sit and wait and have a death spiral?” he said.

In Huntington, West Virginia’s second largest city, Cain and Hannah toured a former coal train refurbishment factory slated to become a manufacturing hub and business incubation space where workers should have been busy with rewiring, brick and roof repair.

“It’s like everything has culminated to the right point, but there’s the starting line, and here’s us,” Hannah said. “We just can’t get to it.”

Cain, who went through a Coalfield Development workforce training herself, said the uncertainty has made the atmosphere at work heavier than usual.

“Just the awareness of what could happen has really affected people’s attitudes,” Cain said. “I’ve seen that a lot of people that come here, that do face barriers, they’re sometimes hopeless they’re not going to be able to build a better life.”

In Morgantown, Daugherty was losing sleep because Libera, the nonprofit she works for, hadn't received reimbursement for a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services grant it uses.

Daughtery, who was placed in state care at 16, said lack of support, low self-esteem, trauma and high rates of depression make the transition difficult for many.

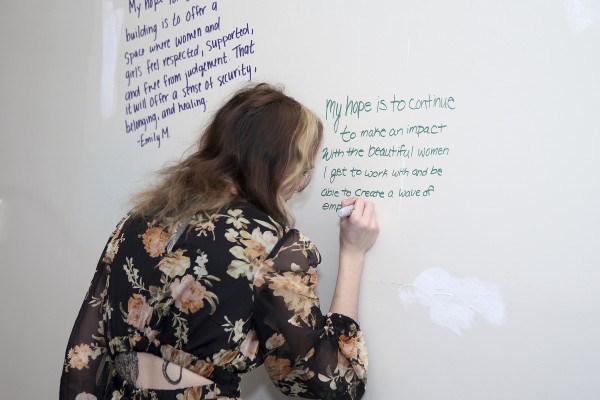

When the organization didn’t receive its scheduled Jan. 31 payment, it had to freeze spending, including for a mental health program serving middle school girls.

With the high need in her area, Daughtery said there are "executive orders right now that are extremely dangerous to the way of life for West Virginians.”

The National Council of Nonprofits CEO and President Diane Yentel said Thursday that some organizations had seen funds restored but many others across the country were still waiting in limbo, and “unfortunately, much of the confusion, chaos, and harm that the directive unleashed hasn’t ended.” The council was among the organizations that sued over Trump’s orders.

The crisis has forced some organizations into quick spending decisions that could have long-term implications.

The Appalachian Center for Independent Living, which provides support to people with disabilities, let staff go, only to rehire them days later when it received a reimbursement.

West Virginia Food and Farm Coalition said it spent a decade building trust with sometimes-skeptical farmers by offering technical support and helping them market their products.

“If that all goes away or if that's all significantly paused, they will lose trust in us," Executive Director Spencer Moss said.

Ryan Kelly, executive director of Rural Health Associations in Mississippi, Alabama and Arkansas, said he thinks the federal freeze was the wrong approach but agrees with what the Trump administration is trying to do.

“Diving in and trying to find the sources of waste, I think that’s a very good thing," he said. “When you’re making changes, there will be problems that happen. But I’m cautiously optimistic that the good will outweigh the bad and there will be some good results coming out of this.”

Alecia Allen, who runs a therapy practice and grocery store in a low-income neighborhood in West Virginia's capital, said lately it's felt like she has been dealing with one crisis after another.

She didn't receive therapy appointment reimbursements for almost two weeks from Medicaid, which insures the majority of her patients. The delay was unusual, she said.

Allen wasn't getting answers from federal agencies about the grants helping her work with farmers to provide local, healthy food to her community at a lower cost. Then a vendor she buys from to stock store shelves said her weekly bill was going up from $500 to $850 because of tariffs.

“It is a huge step backwards, and it is unfortunate to have to digest every day," she said.