I went to bed the night of July 26 with plans to get up the next day and head to Atlanta.

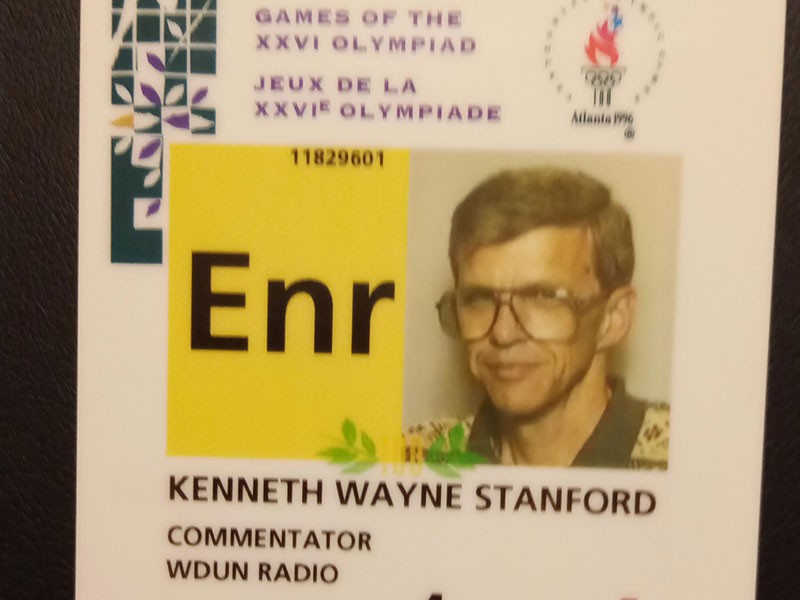

The idea was to give me a break and, using my Olympics press credentials, experience the Atlanta side of the games by visiting several competition sites in the city, not as a reporter, but as a spectator.

I had been working every day since July 17, pulling my early morning news shift from 5:00-9:00 and then heading to the venue to cover the sights, sounds, and competition involving rowers, canoeists, and kayakers.

But, those plans quickly changed in the middle of the night, not long after I went to sleep.

The phone rang and, as was the custom at our house that summer, our 20-year-old daughter, who was home for the summer from college, answered it.

She opened the door to our bedroom and told me that the radio station was on the phone and that there had been a bombing at Olympics park

The person who was working the overnight shift that night, the late John Parks, I believe, told me what had happened. I told him that I would be in at 6:00 to help with the early morning news shift and to brief his relief on what had happened and that I was coming in.

Then, I set my alarm clock to go off at 5:00 instead of 7:00, as planned and tried to go back to sleep. But, as you might guess, sleep was hard to come by.

Question after question raced through my mind. What would this mean to the overall games? There was still a lot of competition left. Would the games go on? How would it impact the Lake Lanier events? How would it affect security at the lake venue? At the sites where spectators, members of the press, and some athletes board shuttle buses to the venue? Was it the start of a coordinated terrorist attack on the games, with more bombings to follow?

I was at the station by 5:30. And, began scouring all the usual sources - ABC Radio, Georgia News Network, Associated Press - for the latest updates. Locally, I began tapping those sources directly involved in bringing the rowing/canoe/kayak competition to Gainesville, keeping the venue running smoothly, and providing security at and around the site. Since this was in the days before AccessWDUN, all my efforts were directed at getting the latest and most accurate information available to our radio audience.

We fielded phone calls from would-be spectators, people who were planning to be on hand for the competition that day - not just at the local venue but other venues where other events were being held.

I don't recall exactly when I left the station, but it was well past noon.

The games went on — albeit it with heightened security — but the story of the competition was overshadowed at times by a constant flow of news about the bombing... profiles of those who had lost their lives in the blast; speculation about who was behind it (and what was the motive); the search for those responsible; how to stay a step ahead of them and prevent something similar from happening again; and, the focus on Richard Jewell, a security guard at the park who was there that night.

As for security at the rowing venue, there were some upgrades, but most were not visible to those arriving at the site. The buses ran their usual schedules, mirrors had been used since Day 1 to check the undercarriages of the vehicles, sheriff's office and Navy SEAL divers continued to check the waters around the docks and the spectator bleachers. The most visible change in security procedures was more thorough bag checks.

And, yes, I eventually found my way to Atlanta (although a week later than planned) and was able to spend a relaxing day taking in the sights, sounds, and some of the competition.

But, as I wandered the streets always in the back of my mind was what had happened in the early morning hours of July 27 and, with those responsible still at large, thoughts of what could still happen.