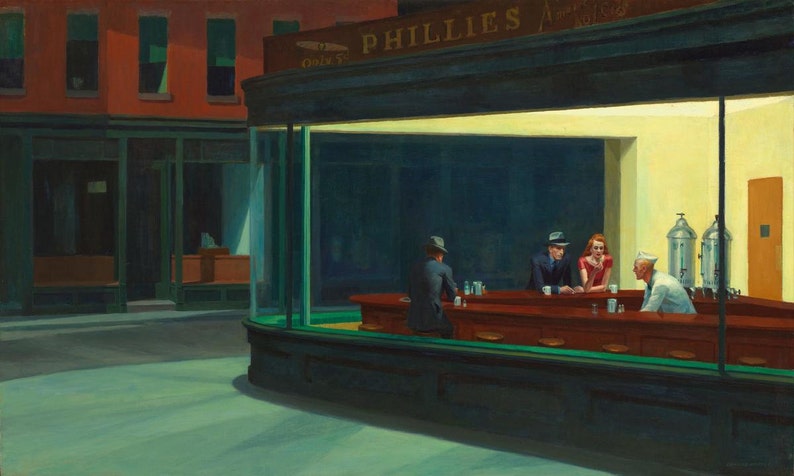

The man with the hawk-like pointed nose sits next to the woman in the polka-dotted dress. Their hands almost touch, but not quite. At an adjacent counter, we see a man dressed in a dark suit, his eyes in a book. The only other occupant in the diner is the soda jerk, hunched over as he washes a dish or prepares an order. We can't tell which. And outside, the streets are dark and deserted. No other eyes exist to take in the advertisement for 5 cent Phillies cigars.

I first gazed at Edward Hopper's work "Nighthawks" when it was a game piece in the Parker Bros. family board game "Masterpiece." I admit that it was that cigar ad that attracted me first, but then I began looking at those figures. They were together but alone. What brought them to that place on an empty street in the late hours of a waning evening? What were their stories? Why do I care?

I finally gave in to my desires and purchased a print of "Nighthawks," and hung it last week. I love it, and find something new each and every time I gaze at it, and I wonder anew. I began to look at Hopper's other work. Hopper, like Norman Rockwell, was a keen observer of American life in the 30s through the 50s. But unlike Rockwell, Hopper is detached from any kind of nostalgic sentimentality. His figures are lonely icons in surroundings that are familiar to all of us. Gas stations, train depots, hotel rooms, even extinct business locations such as automats portray these forlorn figures seemingly trapped by their innocent looking surroundings.

Evidently, I'm not alone in my fascination with Edward Hopper. Lawrence Block, the acclaimed mystery writer, gathered together a smattering of his peers, assigned each of them a painting, and had them write short stories to fill in the backstory suggested by Hopper's work. Jeffery Deaver, Joyce Carol Oates, Craig Ferguson, and even Stephen King jumped on board with little or no hesitation, according to the editor's introduction. I purchased the audiobook version, so as I study the painting and listen to the spoken word, I find myself participating in a sort of "Night Gallery" home edition.

The works of Edward Hopper especially resonate today, in a world where social isolation is supposed to be the new normal. As we alternately rail against then cheer the edicts pro and con socialization, we can gaze at people who existed in a man's imagination far before we'd heard of COVID 19, just as alone and isolated as we are today.

In a classic episode of "Star Trek," Mr. Spock is briefly spared from his own isolation through the influence of alien spores and is permitted at last to fall in love. Upon being freed from that influence, he tells his forlorn girlfriend that "if there are self-made purgatories, then we all must live in them. Mine can be no worse than anyone else's."

When the veil is lifted from our imposed isolation, how will you respond? Will you forever abandon the habits of hugs and handshakes? Will you forsake the movie theater for the comfort and isolation of home video? Will you still bristle with irritation when the eight year-old child in front of you at the checkout line steps on your foot heedlessly while he needles his mother for a Snickers bar?

If you're like me, you're taking some time during this period of aloneness to think about how much you appreciated crowds, the unexpected smile and wave of a complete stranger, and the firmness of a human embrace, even from Uncle Lou who smelled like a pack of Marlboros.

Those that know me are aware of my opinions regarding our coronavirus situation, so I won't bring them here. My concerns here are primarily of where we go afterwards. What's it going to be for you? Rockwell or Hopper?