There are a lot of stories out there about a lot of race tracks that, after years of high speed action, finally succumbed to growth, financial woes or simply to the elements.

But there are not a lot of stories about tracks coming back after almost half a century of being abandoned.

Banks County Speedway is one of the latter.

Located just south of Baldwin, Georgia, in rural Banks County, the speedway was long the stuff of legends, with a racing story all its own.

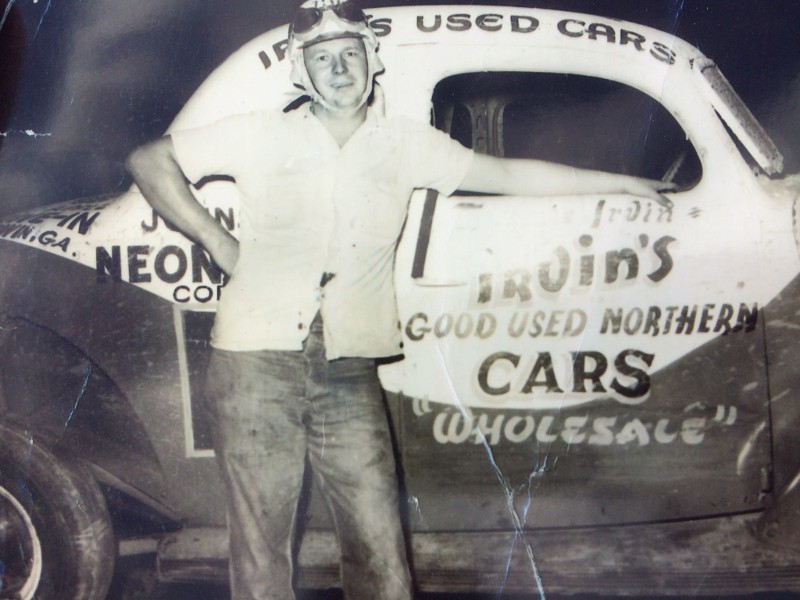

It was built by Tommie Irvin (not to be confused with his cousin, Tommy Irvin, who was Georgia’s long serving Agriculture Commissioner). Irvin, best known in the county for his rural store selling outdoor wear or for his prowess training dogs, had roots that went straight to the birth of NASCAR.

Irvin was a pioneer race car driver, along with his best friend and fellow North Georgia native Swayne Pritchett.

Irvin was born and went to school in neighboring Habersham County. He joined the Army when he was 18 years old in 1943, serving as a sergeant in the infantry during World War II. He was awarded the Bronze Star, among other honors, and was honorably discharged in 1946.

Like many young men of his generation, he had gotten a taste for action while serving his country, and found that racing stock cars on the local tracks fit the bill when he came home.

He was introduced to the sport though Pritchett and Habersham County Speedway promoter Pee Wee Dooley. With Pritchett already racing around the area, Irvin decided to join in. The two raced team cars out of Jack Edwards’ Garage in Cornelia, Georgia, with Pritchett driving the number 17 and Irvin in the number 18.

The duo raced around the state in the late ‘40s. Both soon obtained licenses from the new sanctioning body organized in 1948 by Bill France, Sr. named NASCAR. Both competed at Daytona Beach, Atlanta’s Lakewood Speedway and venues all over the Southeast.

Irvin was on hand at the Jackson County Speedway just outside of Jefferson, Georgia on the day that Pritchett lost his life.

Pritchett and Irvin were both competing at the half-mile dirt track on May 16, 1948. Pritchett was fastest in qualifying, won his heat race and then went on to dominate the feature en route to the win.

But on the cool down lap, Pritchett made heavy contact with another car, sending his Ford tumbling end-over-end. He was thrown from the car when his seatbelt broke, dumping him hard on the track’s surface.

Irvin was the first one to reach him, and begged his friend to lie still and wait for the ambulance. But, to the amazement of the crowd, Pritchett got up and walked to the ambulance.

Swayne Pritchett would die shortly thereafter, a broken rib doing more internal damage with every step he took after getting up.

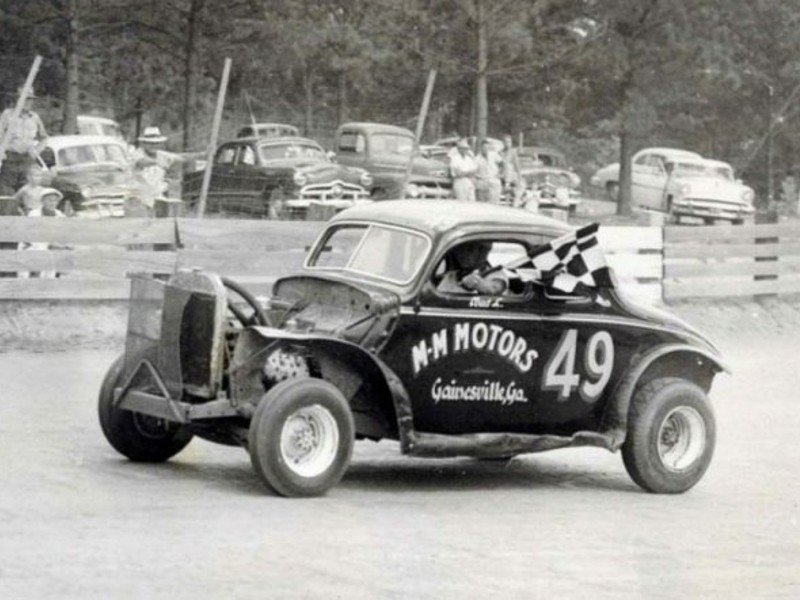

Irvin continued to race, and continued to win. In 1954, he was the Southern Racing Enterprises Association Champion, competing at the Georgia’s Gainesville Speedway, Toccoa Speedway, Dallas and Atlanta’s famed Peach Bowl, among others.

But his biggest win came on Labor Day of 1955 when he won a 100-lap event during the Southeastern World’s Fair at Lakewood Speedway.

With some 60 cars in the starting field, Irvin’s car was in a class all its own. Driving a car owned by Cornelia, Georgia’s Chester Barron, Irvin was able to pass his competitors on the inside line, and could even rim-ride on the outside to bypass slower cars.

During a late pit stop, Barron complained to Irvin that he was going to blow the engine if he didn’t slow down. Irvin replied that he wanted to lap the field before the end of the day.

Irvin got his wish. He bested the field by a full lap, taking home the biggest racing payday he had ever seen in his life.

He took a portion of that money, travelled to Chicago and bought a GranCorp racing engine from Andy Granatelli, who would later become synonymous with racing with his STP engine additive, sponsoring legendary racers Richard Petty and Mario Andretti.

You can add Tommie Irvin’s name to that list of drivers, as he spent several weeks racing Granatelli’s cars at Soldier’s Field over the summer.

When he came home, he took the other portion of his Lakewood winnings and decided to build a race track on part of his property in Banks County, Georgia.

Irvin teamed up with his brother Jackie and with Sheldon Gailey in building the track. Irvin had the land, and Gailey had a relative who was in the grading business. The track opened early in 1956, with racing set for Wednesday nights.

Keep in mind, there were not a lot of extracurricular activities in rural Georgia in the mid 1950s. Television was just beginning to come into its own, the Braves were still in Milwaukee and you had to travel to a larger town on city to go to the movies.

So going to the races was the pastime for many people, with tracks operating all through the week. You would race at Toccoa Speedway one night, and then go to Athens Speedway on another, then to Banks County a third night and it would all culminate with the Sunday night races at the Peach Bowl.

“It was the hot bed of racing in the state,” said racing historian Mike Bell. “When you throw in Boyd's Speedway in Ringgold, Cleveland Speedway in Tennessee, East Park Speedway, Twin Lakes in Elberton, Georgia and the nearby tracks in the Carolinas, it was a dream situation for fans and drivers.

The quarter-mile dirt track held its own, and brought out some of the top drivers of the day, including NASCAR aces Gober Sosebee, Jack Smith, Ed Samples and the famed Flock brothers, Tim, Bob and Fonty – all members of the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame now.

“All of the top drivers ran there,” said Bell. “Bill York, Bud Lunsford, Charlie Mincey, Charles Padgett and Charlie Burkhalter.”

The track even drew some of the top Tennessee speedsters, including Harold and Freddy Fryar, Freddie Smith and Friday Hassler.

In fact, two of the all-time great drivers from Georgia competed their throughout there careers.

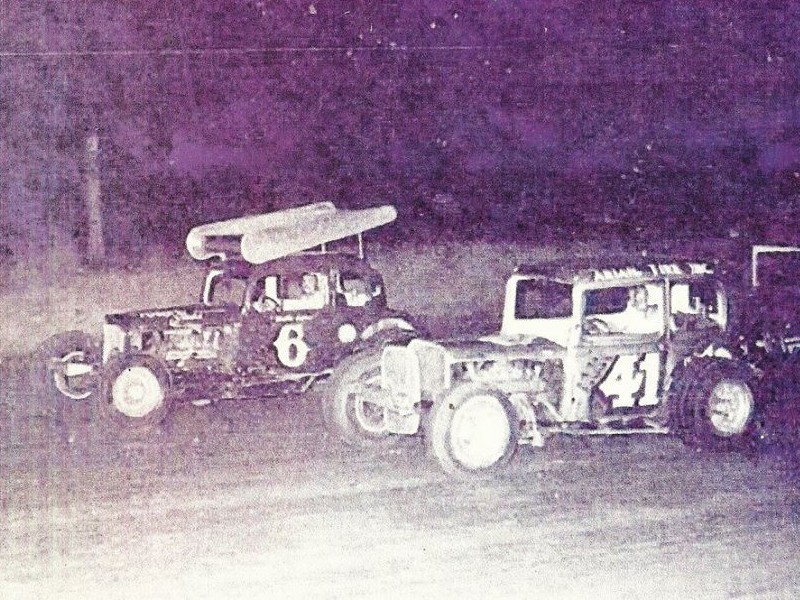

Gainesville, Georgia native Bud Lunsford won one of the first of his 1,139 feature wins rat Banks County, and would compete there in Late Models and the famed winged “Skeeter” Super Modifieds in the ‘60s.

Baldwin, Georgia’s Buck Simmons got his start at Banks County Speedway inauspiciously, piloting the water truck to wet down the dirt surface. He would move on the competition side soon thereafter, winning some of the first of his over 1,000 career feature wins at the quarter-mile raceway.

Both men are now enshrined both in the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame and the National Dirt Racing Hall of Fame.

The racers weren’t the only celebrities to show up at the track. Paul Anderson, billed as the “World’s Strongest Man”, would often travel down from his home in Toccoa to take in the races.

So too would baseball hall of famer Ty Cobb, a Royston, Georgia native. But with Cobb’s temperament, Irvin tried to keep his presence quiet, sitting him off by himself so no one would bother him.

“Cobb’s nephew would bring him because I don’t think he was able to drive for some reason,” Bell said. “Jimmy Mosteller, who was the track announcer, said that he never mentioned that Cobb was there, because he carried a .38 pistol with him everywhere.”

Along with the drivers, Banks County Speedway could also boast some top action of the day.

“It was a very racy place but not really fast,” said Bell. “But the drivers always put on a good show for the fans.”

Sometimes putting on a good show included a gimmick dreamt up by Irvin to entertain the crowd. One night, they held a donkey race, with a few ringers bringing in horses to compete. The track also hosted jalopy races that included running the final lap in reverse, and demolition derbies that left the track littered with debris and the fans buzzing with excitement.

One night, the fans were even entertained by a driver named Red Green who would play a fiddle for the crowd between races.

But at the heart of it all were the races.

In one event, Bud Lunsford was penalized for making contact with another car. Lunsford, who was a constant winner around the southeast at the time, charged back through the pack and scored the win anyway.

Another night, a driver lost control and went through the fence. Without damaging the car, the driver turned around, only to find the part of the fence he had gone through had fallen back into place. He drove the car around outside trying to find a way back through to get back onto the race track.

Then there was the night a driver got crossed up down the backstretch, with his car tumbling side over side through the third turn, over the fence and into the parking lot. He walked away with only a bruised ego.

Fortunately, no one was every badly injured at the Banks County Speedway, a rarity in those days. Reportedly the only serious situation came when a driver was burned by hot water from a broken radiator hose, resulting in a $37 hospital bill.

The track continued to race through the 60s, when the winged “Skeeter” Super Modifieds became the most popular form of racing in Georgia. With the drivers moving from track to track through the week, Banks County was in its heyday.

At that point, the only thing that hampered it was the same thing that still hampers every race track today – wet weather.

Rain can be a burden to any type of race track, but none more so than dirt tracks. Track officials work hard to prepare the speedways with just the right amount of water to make for a good racing surface. But too much water – especially at the wrong time – can leave the track surface soupy and wipe out a race night.

However, with an asphalt surface, as long as you have enough time to dry the track, you can have all the rain you want and still have a chance to race.

After enduring a wet, rainy season in 1964, Irvin decided to pave the Banks County Speedway, with the promise from drivers at the asphalt Peach Bowl in Atlanta to come north to compete.

“Tommie said he had promises from the drivers. They came but the fans did not,” said Bell. “The economy in North Georgia was still based on the dirt farm.

“All the drivers liked the asphalt, but no fans showed up for the races.”

After two years, the pavement was plowed up, and in 1967, Banks County went back to dirt.

“He went back because all his fans wanted it,” Bell said.

The speedway would run through the end of the decade, but a tragedy in another part of the state spelled disaster for it and several other race tracks in Georgia and around the country.

During a drag racing event at the Yellow River Drag Strip in Covington, Georgia in March of 1969, a car went out of control and went into the crowd, leaving 11 people dead and upwards of 50 others injured.

The Georgia State Legislature responded the next year by passing laws that said racetracks had to have liability insurance of at least one million dollars. Fire marshals started visiting tracks, insisting on changes including replacing wooden fences with guardrails or concrete retaining walls, and taking out the old wooden grandstands, to be replaced by concrete or metal seating. Changes that were costly, and put many race tracks out of business.

Among them was the Banks County Speedway. Irvin had the insurance, but the cost of the changes against the cost of running the track just did not make economic sense to him.

So after one more race in 1971, the Banks County Speedway was closed.

The property sat overgrown for 44 years, littered with old cars, derelict trucks and remnants of the past. The outline of the track was still there, and through the brush you could still see the old tower and concession stand. The light poles, with the lights still attached, still stood there, along with the old seats and the wooden guardrails. Silent to everything but the occasionally herd of goats that were let onto the property to graze.

Tommie Irvin continued to be a race fan and enthusiast the rest of his life. He was inducted into the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame in 2009. He passed away on December 5, 2010.

But his story, and the story of the Banks County Speedway, does not end there.

In 2015, Irvin's family hit upon the idea of resurrecting the old raceway. But not with the idea of racing, but rather of remembering.

Inspired by the success of the annual Athens Speedway reunion, the family made the decision to clear the land that the Banks County Speedway sits on, and returning it to the way it looked in its heyday, with the goal of holding their own annual reunion.

The brush was cut out, the trees were cut (with the exception of one that grew up through a derelict Volkswagen Beetle), and the track was re-graded. The wood from the trees was used to make boards to rebuild the official’s tower, flag stand, ticket booth and even the restrooms.

On Saturday, May 9, 2015, the Banks County Speedway lived again. Race cars were parked in the infield, fans walked the track and many asked when the first race would be held.

While the family insists no racing competition will ever be held there again, it stands as a tribute to Tommie Irvin and his legacy, along with those drivers that competed at the track.

“I just thought our old track is just sitting there growing up in trees and it’s just a shame to not proceed with preserving the old foundation of stock car racing,” said Bobby Irvin, Tommie Irvin’s son in a 2015 interview.

“Hardly ever do you see tracks like this restored,” said Bell. “It to me is as important as someone restoring the Indy 500 winning car from 1961.

“The family and the people that worked with them should be commended for what they did.”

For former driver Bobbie Whitmire, it brought back many memories.

“I hit a wall down there one time,” the Gainesville, Georgia native said in a 2015 interview. “(I) Turned (the car) over there one time. I remember Tootle Estes climbed that bank over there and rolled the whole straightaway. Some of those old memories are coming back.”

These days, that’s what the Banks County Speedway stands for. Memories that faded, but with a little work, came back in crystal clear focus.