It’s well known that several Georgia racers were pioneers in the early days of stock car racing. In fact, Georgians dominated the decade of the 40s on the old Daytona Beach and Road Course.

Lloyd Seay, Roy Hall, Gober Sosebee and Bernard Long, all natives of Dawsonville, Georgia, scored victories on the hard-packed sands. They were joined by fellow Georgians Red Byron and the Flock brothers - Tim, Bob and Fonty – who all earned wins at Daytona.

All these men are members of or have been recognized by the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame. But one name is missing from that list. A Gainesville, Georgia native, journalist and Open Wheel racer who was one of the first Georgians to win at Daytona not once but twice before any of the aforementioned speedsters had begun driving competitively. And he still holds a speed record on the sand.

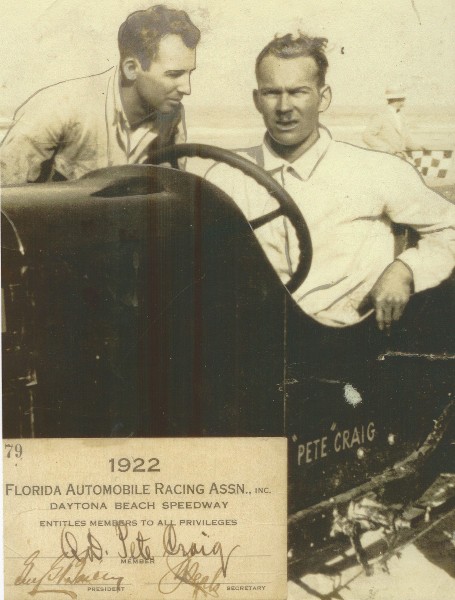

Pete Craig was born in Gainesville on February 9, 1902. His father, William Harvey Craig, was the editor of the Gainesville Eagle newspaper for several years.

Craig left Georgia to enlist in the Army at the age of 14 - believed to be the youngest to serve at that time - to fight against Poncho Villa in the Mexican Border wars. Soon after, he would fight for his country in World War I, serving under John J. "Black Jack" Pershing in the fight in France.

"Had to wear my scout uniform the first month in the Army until they could get a GI uniform to fit me," Craig said in an interview with the Thomasville Times-Enterprise published April 1, 1967.

His older brother, Britt, was a pilot in the war, and lost his life in 1919 at 23 years of age. Before joining the war, Britt was also a journalist, working for the Atlanta Constitution and for the New York Sun. He gained notoriety while reporting on the Leo Frank murder case in Atlanta. Both Britt and his father are buried in Alta Vista Cemetery in Gainesville.

After the war, Craig followed his father’s footsteps in becoming a journalist. He would work for the Gainesville Eagle, as well as the Atlanta Constitution, and would later work with the United Press bureau in Washington D.C. He returned to Georgia to go to work at the Columbus Inquirer in South Georgia.

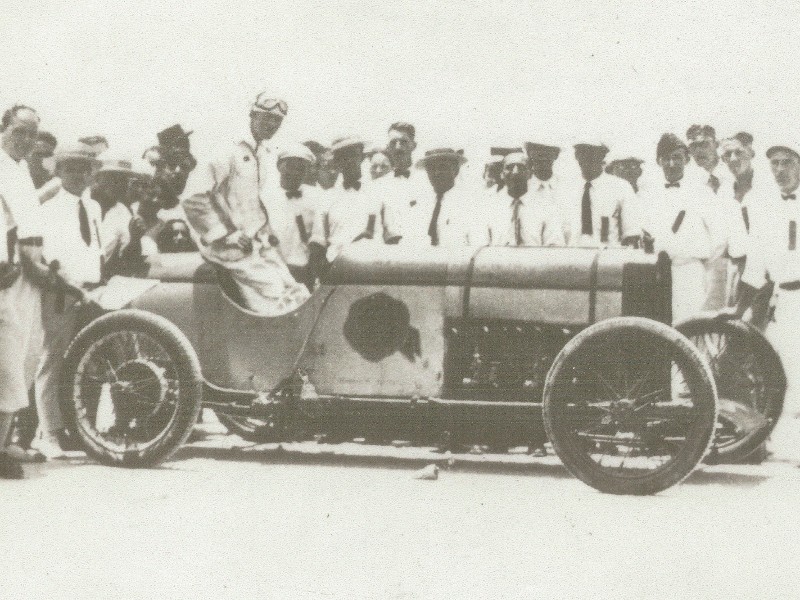

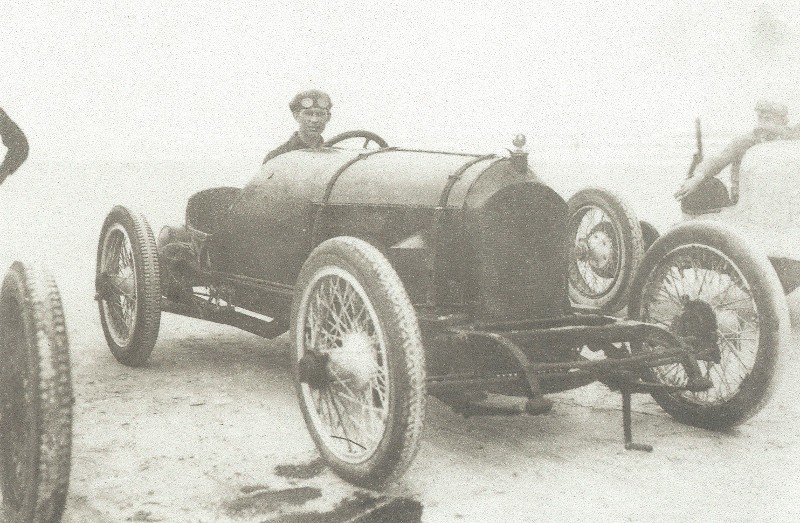

In 1921, he found a new hobby – auto racing. He raced several times at Atlanta’s Lakewood Speedway in Open Wheel cars. He also traveled down to Daytona Beach to compete in early events on the beach course. This was many years before Bill France, Sr. began organizing stock car races there.

Craig became the first known Georgian to win on the beach on June 11, 1926, when he scored the victory in a 10-mile race held on the hard-packed sands. It was part of a series of races held during the “Summer Frolics” event.

Daytona Beach would become a favorite for Craig, and he would work for a period of time for the local newspaper. It would also be the site of the only racing related injury in his career – but not in an automobile.

Craig’s love for speed also translated over to two wheels, as he raced motorcycles as well. While testing for the Indian factory team at Daytona, he hit a school of jelly fish that had washed up on the beach. The resulting crash left him with a broken collar bone.

Back on four wheels, Craig continued to compete in races on the beaches at Jacksonville and Cocoa Beach, as well at the Fulford-Miami Speedway, a 1.25-mile wooden board race track with 50 degrees of banking in the turns (in comparison, the banking at Daytona International Speedway is 32 degrees). The track, which was located not far from the current location of NASCAR's Homestead-Miami Speedway, saw speeds in excess of 110 mph - making it, at the time, the fastest race track in the world.

Craig would return to victory lane at Daytona Beach just over five years later in a record setting race on September 13, 1931.

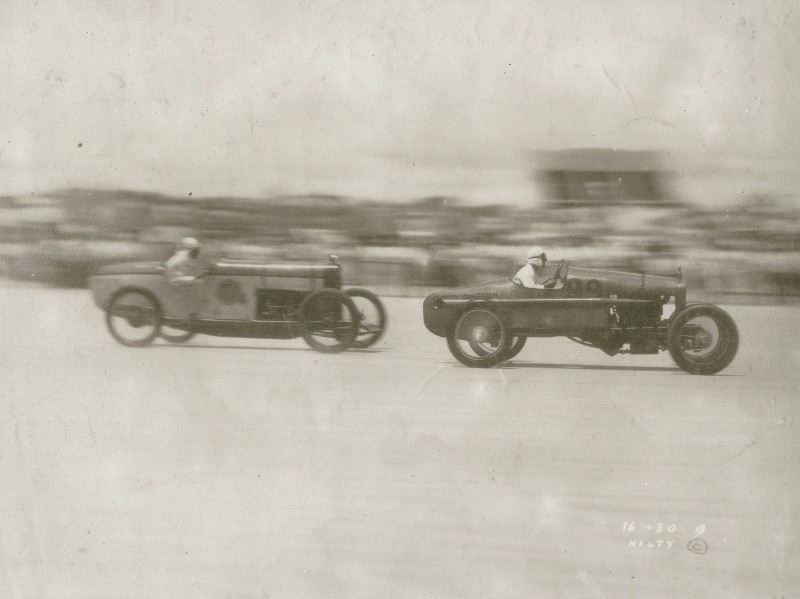

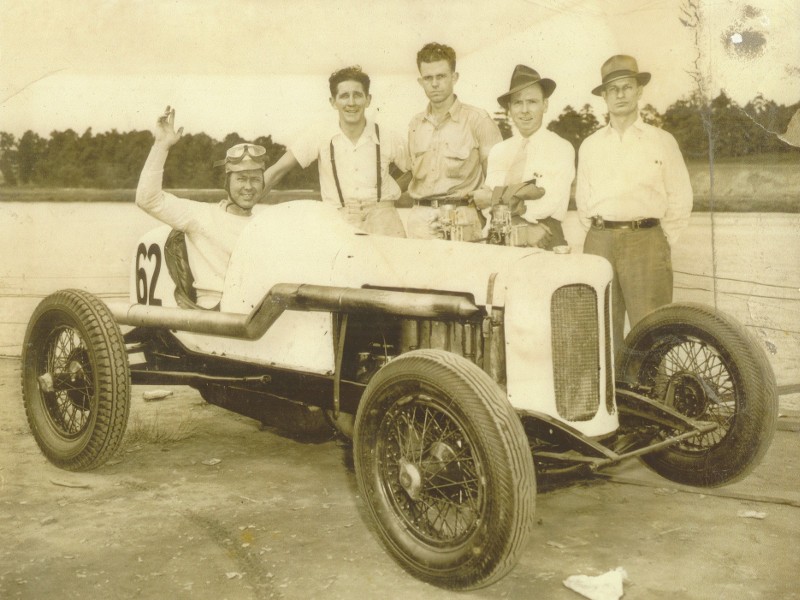

Driving the white No. 7 Perfect Circle Special Chrysler 60, Craig trailed Daytona Beach native Walter Johnson for 26 of the 30 laps that made up the distance. Craig twice almost saw his race go away.

The first incident occurred on lap 15, when the muffler on the No. 7 broke loose, flying through the air. It just missed his head, but the hot piece of metal struck him in the shoulder. Despite this, he stayed in the throttle.

The second close call came a few laps later, when Craig and Florida racer W.G. Faulk locked wheels as they race through the north turn. Both drivers were able to regain control and continued on.

Craig made only one pit stop on the day, stopping with 10 laps to go to allow his crew to add water to his radiator. That stop appeared to hand a sure victory to Johnson.

But with four laps to go, Johnson’s car broke a ground wire, sending him to the pits and handing the lead to Craig. From there, Craig led the rest of the distance, crossing under the checkered flag waving and smiling to the crowd. He pocketed $333.37 for his efforts – equal to about $6,000 in 2020.

More importantly, Craig covered the 100-mile distance in a record time of one hour, 25 minutes and 45 seconds at an average speed of 70.2 miles an hour. That record is believed to still be the fastest for a 100-mile race for Open Wheel cars on Daytona Beach.

Craig raced across the southeast in a Flathead Ford powered racer prepared by Atlanta’s Bob Reed. In those days, the Open Wheel style roadsters would compete around the state at tracks like Lakewood, Atlanta Speedway (a short-lived, high banked half mile dirt track in the shape of a circle built at Paces Ferry Road at the Chattahoochee River), and Central City Speedway in Macon, Georgia (a one-mile track that still exist today as a walking track).

There were also several areas in Georgia that would hold races during county fairs on tracks originally intended for horse racing, including Savannah, Albany, Eastman and Sylvania.

In addition, there were several tracks around the south that hosted the open wheel racers, including the original one-mile fairgrounds track (now cut down to 5/8 of a mile) in Nashville, Tennessee, along with Chattanooga and Knoxville in Tennessee, Montgomery and Birmingham in Alabama, and Columbia and Spartanburg in South Carolina.

“That was kind of the end of horse racing in the south,” said racing historian Mike Bell.

The distinct problem in putting together a full set of statistics for Pete Craig is the lack of information available on racing prior to World War II.

“Most of the newspapers were not equipped to write about automobile racing,” said Bell. “It was new to most. They got the names wrong, the driver's (hometowns) wrong. They did not understand the partnership between and owner and a driver. But they should have because relationships between a horse owner, a trainer and jockey were the same.

“They did not know how to tell the stories.”

While North Georgia is well known for turning out a myriad of talented stock car and even sports car racers over the years, finding a pre-war successful Open Wheel ace from the region is rare.

There were several drivers from around the state that Craig likely competed against, including Speedy Morelock and brothers L.J. “Foggy” Calloway and Buddy Calloway, all from Macon, C.J. “Crash” Waller of Blakely, Don Kenney of Atlanta, Glenn Roberts of Atlanta (not to be confused with Glenn “Fireball” Roberts of NASCAR fame, who was from Florida), and brothers Jack Argoe and Wesley Argoe, also both of Atlanta.

But as far as Northeast Georgia goes, Craig was the exception.

“They were pretty rare, like finding an asphalt track in the state is today,” said Bell. “The talent pool was shallow. Speedy Morelock, who is in the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame, is one that comes to mind. But when you got out of Atlanta and Macon, there were none.”

A chance meeting while racing at Lakewood Speedway with Atlanta Journal managing editor Jim Pope landed Craig a job at the paper that would last for the next 12 years.

That scaled back much of his barnstorming as far as racing went, but he continued to race at Lakewood until the beginning of World War II. Along with racing in open wheel cars, he dabbled in the new southern racing fad – Stock Car racing. In addition, he worked as a race official at Lakewood.

Craig did make one more trip to Daytona Beach, where he competed in a Stock Car race on March 19, 1939 promoted by Bill France, Sr. and Charlie Reese. It’s unclear where Craig finished, as only the top six finishers were reported on. Sam Rice, wearing a full-brimmed hat rather than a race helmet, took the win with France finishing second.

When World War II broke out, Craig was drafted back into the Army, but didn’t serve in combat due to health reasons.

Meanwhile, as a reporter, his work had long lasting effects, including leading to a number of prison reforms in the state of Georgia.

Craig finally left the newspaper business to take a job at the War Labor Board in Atlanta. That led to a series of government jobs until he landed in Thomasville, Georgia, where he served as the Information Officer of the Office of Civil Defense. He would stay in that position until his retirement on April 8, 1967.

He retired to Panacea, Florida to pursue another passion – saltwater fishing.

"I'm finally throwing in the sponge. And I don't intend to hit a lick at even a rattlesnake for six or eight months," Craig said in an interview with the Thomasville Times-Enterprise published April 1, 1967.

As to his racing history, Craig was decidedly humble and low key about his history behind the wheel.

Craig had two sons, Pete Craig, Jr. and Britt Craig.

In a 2006 letter to Mike Bell, Craig, Jr. shared some stories with about his father. Craig, Jr. said he remembered finding a trophy in the attic of the family home from a Labor Day stock car race at Lakewood Speedway in the attic.

"Dad said it was a roadster, new for whichever year it was and they had their race car engine in it," Craig, Jr. wrote. "I kidded him for cheating, so he said, 'the guy who won had his race motor in his too.' He won $200. Good money during the depression."

Unfortunately, Craig, Jr. wrote that the trophy is likely lost forever.

"I asked him where the trophy was six of seven years later," Craig, Jr. wrote. "He thought about it and said 'We left it in the attic when we moved.' Then he mumbled something about 'Never kept the trophies anyway. You couldn't eat the damn things.'"

After his retirement, Craig relocated to Panacea, Florida, which is about 50 miles south of Thomasville. He passed away November 12, 1968 at the age of 66 of natural causes. He is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Perry, Georgia.

Craig, Jr. wrote that his father said on his death bed, "Wherever I'm going, I'll have a lot of friends there."

Pete Craig has been nominated to the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame in Dawsonville, but thus far has yet to make the cut to be inducted. He also has yet to be recognized by the Northeast Georgia Sports Hall of Fame, located in his own hometown at the Northeast Georgia History Center.

But hopefully one day in the future, Gainesville, Georgia’s racing pioneer can be memorialized as a motorsports trail blazer who remains one of the fastest ever on the beach.