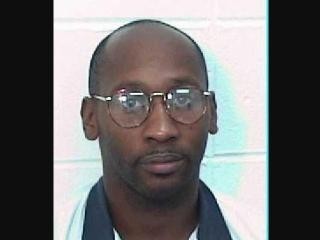

ATLANTA - Death row inmate Troy Davis will get a rare chance Tuesday to press for a new trial in a case that has drawn fierce protest from death penalty opponents who say the state of Georgia could execute the wrong man.

Defense attorneys will ask the state Supreme Court to grant Davis a new trial in light of testimony his lawyers say will prove his innocence and implicate another man. Prosecutors, meanwhile, will argue the case is closed and new evidence can't be considered.

The arguments will test a Georgia law - the only one of its kind in the U.S., experts say - that allows inmates to seek a new trial after exhausting other appeals. And it could force the court to stake a position in a long-standing debate over adopting statewide eyewitness identification standards.

The case began in 1989 when 27-year-old Savannah police officer Mark MacPhail rushed to help a homeless man who had been pistol-whipped at a Burger King parking lot next to a bus station where the officer worked off-duty as a security guard.

Moments after MacPhail approached Davis and two other men in the parking lot, he was shot in the face and the chest and fell to the ground, mortally wounded.

Witnesses identified Davis as the shooter. A jury convicted him in 1991 and sentenced him to death. At the trial, prosecutors said he wore a "smirk on his face" as he fired the gun, according to records.

But Davis' lawyers say new evidence could exonerate their client and prove him a victim of mistaken identity. Several witnesses who initially testified against Davis have since recanted or contradicted their testimony. And three others who did not testify have said another man, Sylvester "Red" Coles - who testified against Davis at trial - confessed to the killing.

Coles refused to talk about the case when contacted by The Associated Press during a recent Chatham County court appearance on an unrelated traffic charge, and he has no listed phone number.

Prosecutors call the witness statements "suspect," and say Davis' attorneys have failed to prove why he should be granted a new trial. They also say some of the witness affidavits simply repeat what a trial jury has already heard, while others are irrelevant because they come from witnesses who never testified.

The case puts Georgia's high court, which voted 4-3 to consider Davis' appeal, on unfamiliar footing. Any decision would likely rely on a 1980 ruling that suggested a new trial may be necessary if new evidence "would probably produce a different verdict."

Donald E. Wilkes Jr., a University of Georgia law professor who specializes in the death penalty, said Georgia is the only state that permits defense attorneys to ask a judge to grant an extraordinary motion for a new trial even after they've exhausted all other appeals.

Even then, the evidence must meet strict standards, and the court has proven reluctant to grant new trials. Wilkes said the only death row inmate exonerated using such an appeal was Jerry Banks, who was convicted of a double murder in 1974 and spent six years on death row before the Supreme Court unanimously overturned his sentence and released him.

But Davis' attorneys will likely face a skeptical audience, particularly because three of the court's seven justices voted against hearing an appeal. "Three of these justices didn't think this case was worth hearing to begin with," Wilkes said. "It seems it would be very hard to persuade them."

The outcome will be closely watched in the Georgia Capitol, where Davis' case is frequently cited by advocates of new statewide standards to govern eyewitness identification. Death penalty critics, meanwhile, present Davis as an example of the uncertainties of capital punishment.

Tuesday's hearing is expected to draw dozens of protesters from Amnesty International, which has championed Davis' case. The group organized a rally in support of Davis on Monday night and has on its Web site a recording in which Davis professes his innocence.

"I would never take another human being's life," Davis says in the recording. "My family is in mourning, the victim's family is in mourning and the truth is still locked in because I didn't get justice."

The case has also attracted legal heavyweights such as Harvard Law School's Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice, which filed a brief contending that the new evidence "overwhelmingly favors a new trial."

"It is precisely the sort of evidence for which the extraordinary motion statute was created, and to disregard it would be to perpetuate the most grievous injustice known to our legal system - the execution of a truly innocent man."

---

On the Net:

Georgia Supreme Court: http://www.gasupreme.us

Monday

July 14th, 2025

4:31PM