Many historians and others consider 1963 the year that gave unofficial birth to the civil rights movement even though the Montgomery bus boycott had taken place eight years earlier and the first notable lunch counter sit-in in 1961 in Greensboro, North Carolina.

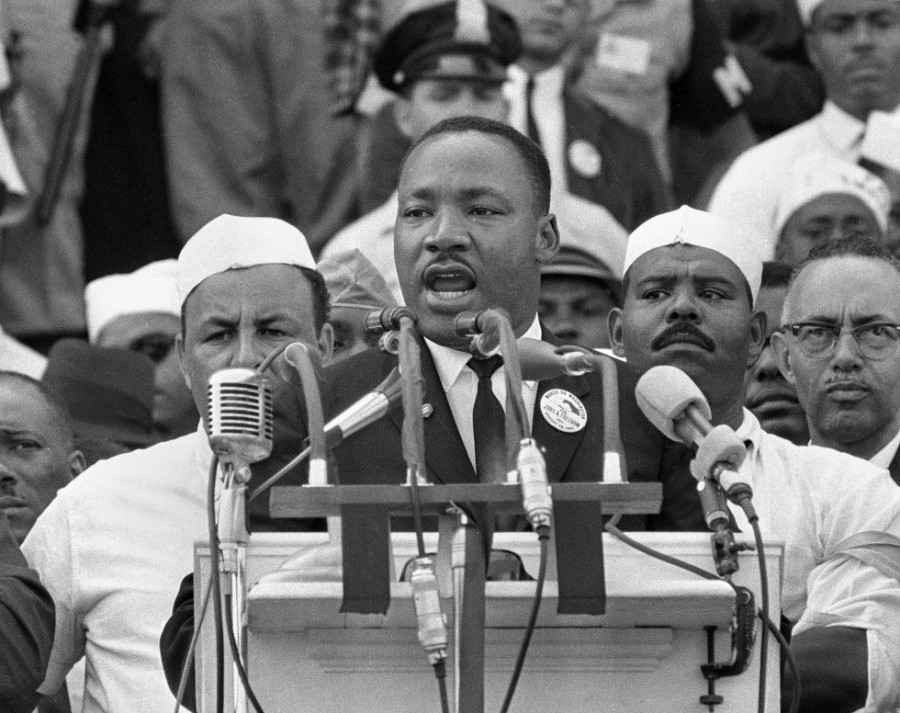

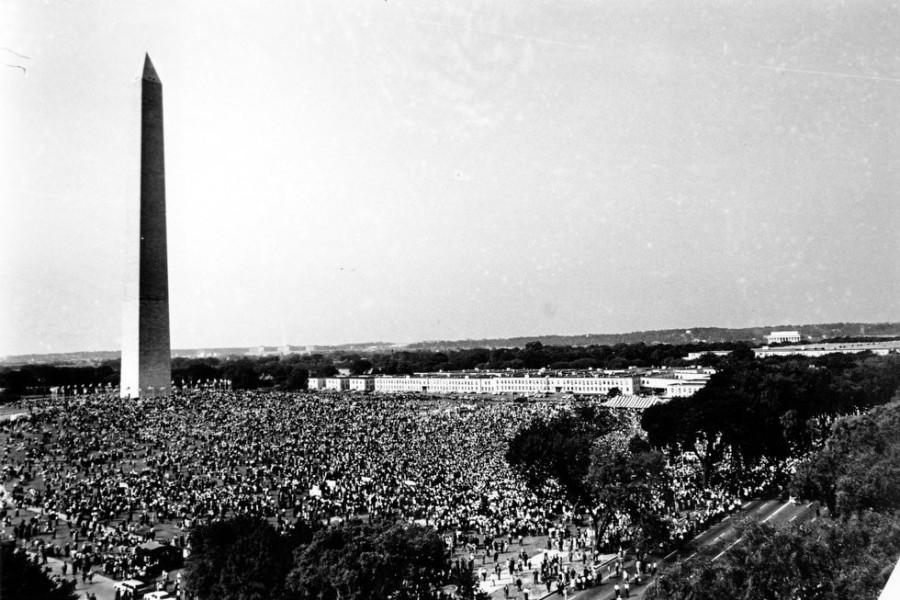

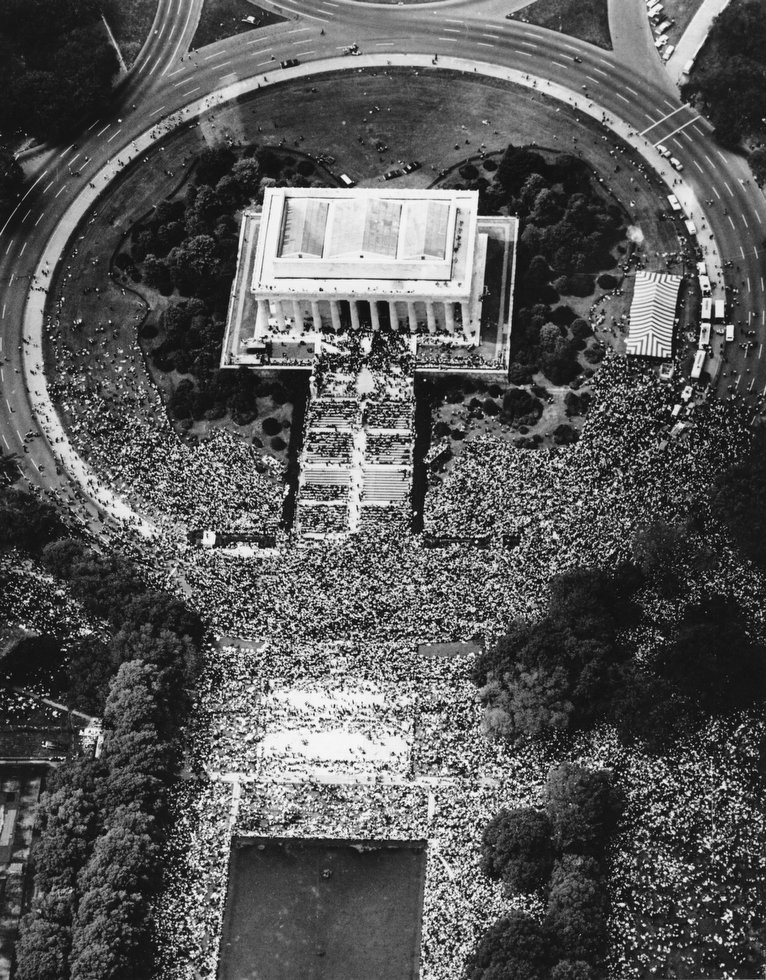

To many, the linchpin for using 1963 as the year the movement began was the March on Washington and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech which occurred Aug. 28 and will be marked with a number of special observances that have already begun and will continue into next week. The event drew 250,000+ people who crowded into the Washington Mall in front of the Lincoln Memorial where King and some of his closest aids were located and from which he and others spoke.

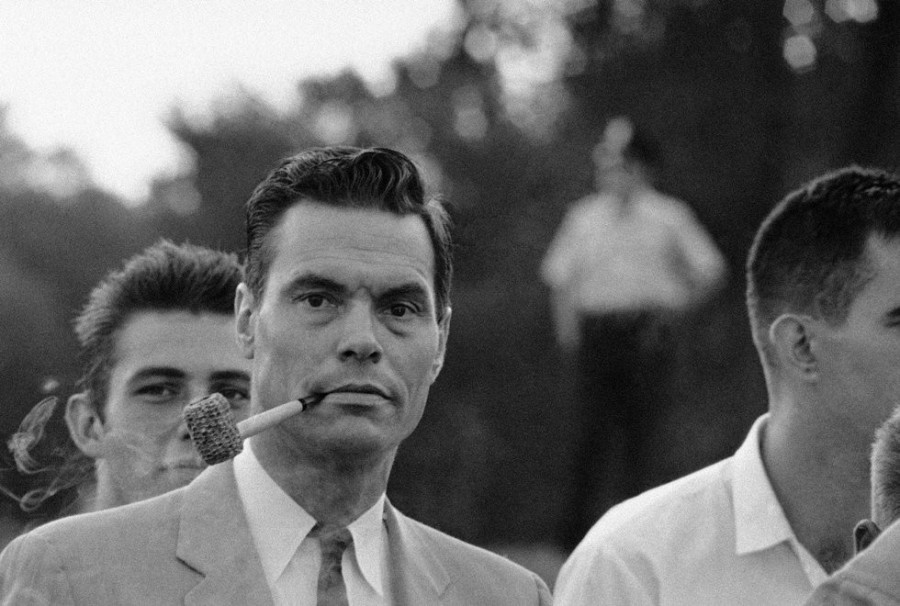

An undetermined number of counter-protesters also showed up, including George Lincoln Rockwell, founder of the American Nazi Party. However he and about 40 of his followers were in civilian clothes and not their usual uniforms. Police denied a parade permit for Rockwell.

GEORGIA'S ROLE

Georgians played no small role in the Civil Rights Movement.

Dr. King was, of course, from Atlanta but there were others including the late Ralph David Abernathy and the late Hosea Williams (both from Atlanta); Andrew Young of Atlanta, who went on to become a U.S. Representative, U.N. Ambassador, and Mayor of Atlanta; and Julian Bond, an Atlanta man, who was refused a seat in the Georgia House of Representatives in 1965 but who eventually was seated after he took the matter the court. In voting to deny him a seat in the House, lawmakers said it was because of his association with anti-Vietnam war sympathizers and not his involvement in the civil rights movement. C.B. King, a lawyer from Albany and no relation to Dr. King, was another prominent black Georgian involved in the civil rights movement. Also playing a key role in the movement as well as the March on Washington was John Lewis, now a Congressman from Atlanta. Lewis was also one of the other speakers at the rally.

The event also drew thousands of other people from Georgia who were not prominent members of the civil rights movement.

Among them was 9-year-old Clinton Brown of Gainesville. According to a book called "Black American Series: Hall County Georgia," written by Linda Rucker Hutchens and Ella J. Wilmont Smith, a picture of Brown, with the American flag and the Washington Monument reflected in his sunglasses, was flashed around the world as part of the global coverage given the march and rally.

BACK IN GAINESVILLE

Gainesville's public school system was still segregated in 1963, nine years after the U.S. Supreme Court declared "separate but equal" schools unconstitutional. But that was not uncommon in the South at the time.

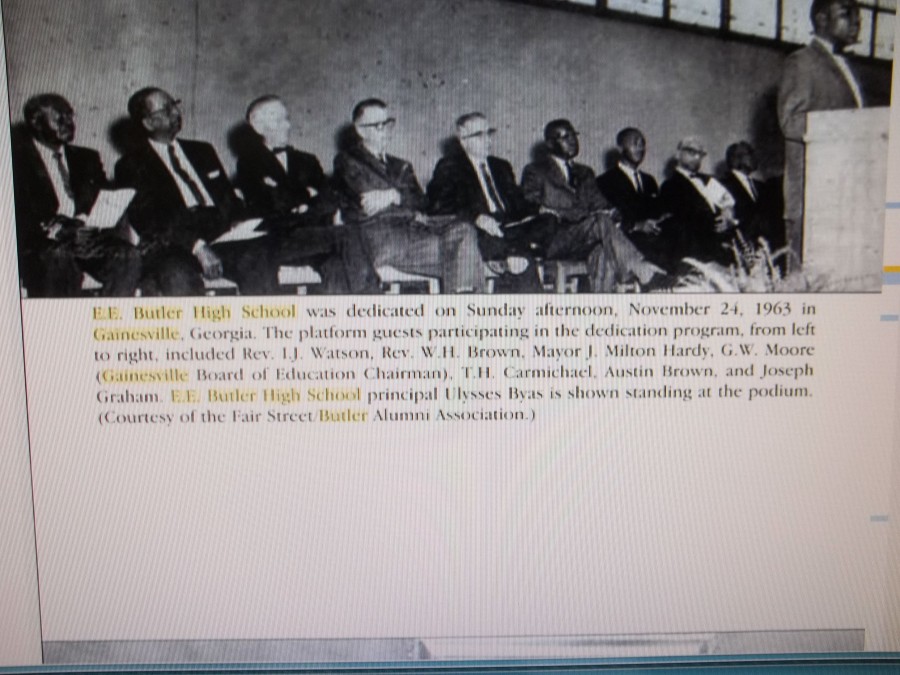

Desegregation of public schools didn't occur overnight. And, ironically, just three months after the March on Washington, city officials in Gainesville gathered to dedicate a new high school to serve the city's African-American population, according to the Fair Street Alumni Association. E.E. Butler High School, which replaced Fair Street High School, was dedicated on Nov. 24, 1963. It closed six years later when schools in the city were desegregated.

One of the people most closely associated with the civil rights movement in Gainesville, at least for the past 40 years or so, is Faye Bush. In 1970, Bush spearheaded a march in Gainesville in honor and memory of Dr. King. It continues each January on MLK Day and Bush still actively participates in organizing it each year and participating in it.

In a 2010 interview with AccessNorthGa.com/WDUN, Bush remembered the court battles and counter-protests by the KKK that her group had to go overcome just to stage the march, which began several years before Martin Luther King Junior Day became a national holiday.

In a 2006 interview just prior to the start of that year's march, Brush said of the day that honors the civil rights icon and his dream "I think he would want us to come together and I think he would want us to be doing things rather than taking a vacation and just saying it's a vacation. We need to be doing things towards his dream."

Bush and others, such as the late Rev. Clarence Waggoner, were also instrumental in getting the Gainesville City Council to create a city holiday in honor of King.

MARKING THE ANNIVERSARY

The observances begin Saturday with a march from the Lincoln Memorial to the King Memorial, led by the Rev. Al Sharpton and King's son, Martin Luther King III. They will be joined by the parents of Trayvon Martin, and family members of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy who was kidnapped, beaten and shot in the head in 1955 after he was accused of flirting with a white woman.

Sharpton has refused to call Saturday's march a commemoration or a celebration. He says it is meant to protest "the continuing issues that have stood in the way" of fulfilling King's dream. Martin's and Till's families, he said, symbolize the effects that laws such as the stop-and-frisk tactics by New York police, and Florida's Stand Your Ground statute have in black and Latino communities.

"To just celebrate Dr. King's dream would give the false implication that we believe his dream has been fully achieved and we do not believe that," Sharpton said. "We believe we've made a lot of progress toward his dream, but we do not believe we've arrived there yet."

President Barack Obama is scheduled to speak at the "Let Freedom Ring" ceremony on Wednesday, and will be joined by former Presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton. Along with their speeches, there will be a nationwide bell ringing at 3 p.m. EDT to mark the exact time King delivered his "I Have A Dream" speech, with which the march is most associated. The events were organized by The King Center in Atlanta and a coalition of civil rights groups.

Separately, a smaller march, led by people who participated in the 1963 event and young scholars and athletes, will make its way from Georgetown Law School in Washington to the Department of Labor, then the Justice Department and finally the National Mall. The group plans to march behind a replica of the bus that Rosa Parks was riding in when she refused to give up her seat.

KENNEDY ACTS

Two months before the Aug. 28, 1963 march, President John F. Kennedy made a passionate statement about the morality of racial equality. He introduced a civil rights law that prohibited discrimination in public accommodations and called for stronger action enforcing the Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which struck down segregation in public schools.

William Jones, author of "The March On Washington," said at the time of the 1963 march, the ideal of racial equality already was accepted by many. The primary goal, he said, was to call for strong federal enforcement of that ideal, and to push for a federal law prohibiting private employers and unions from discriminating against people because of their race.

The current Supreme Court also accepted the ideal of racial equality, Jones said, and stated the need for it in its recent decisions on voting rights, university admissions and employment discrimination cases, but "backtracked" on the ability to enforce that ideal.

"And in a sense that's exactly the situation that organizers of the march were dealing with," Jones said.

WHAT IS WAS LIKE THAT DAY, IN THAT ERA - AND WHERE WE ARE TODAY

In 1963, marchers arrived by bus, train, car and on foot on a weekday, many dressed in their Sunday best. Although marchers were mostly black, the crowd included whites, Jews, Latinos and Native Americans.

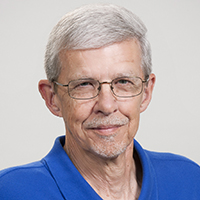

At that time, it was daring to walk through the streets and march in protest, said Phil Schaenman, who was in Washington in 1963 working on the manned space program. An amateur photographer, he had gone out with his camera expecting to see a riot and ended up joining the protest.

"I changed roles from being a spectator to joining in. I didn't realize I had stepped off the curb and joined in," said Schaenman, now a researcher on efficiency in local government at the Urban Institute.

The Economic Policy Institute has been producing regular reports under the banner of "The Unfinished March" to emphasize what it says is the unfinished economic history of the march. Demands at the march also were made for decent housing, adequate and integrated education, a federal full employment jobs program, a national minimum wage that would be the equivalent of more than $13 an hour in today's dollars.

The value of today's $7.25-an-hour minimum wage is $2 less than the minimum wage in 1968, according to the institute.

"To truly honor the march, we also have to recognize the unfinished demands," said Algernon Austin, director of race, ethnicity and the economy program at the Economic Policy Institute.

There clearly is far less overt discrimination today than there was 50 years ago, said Gregory Acs, director of the Urban Institute's Income and Benefits Policy Center. On the other hand, eliminating overt discrimination has bred insensitivity to the impact of policies that on the surface are said to be race-blind, such as jailing people for minor drug offenses or creating barriers to voting to make elections cleaner and more fair, Acs said.

"We still have a ways to go, but that we can have the conversation and continue having the conversation - there's clearly progress," Acs said.

(The Associated Press contributed to this story.)

Monday

June 30th, 2025

6:15PM