WARSAW, Poland (AP) — Wanda Kwiatkowska eagerly read reports on Wednesday morning about the U.S. presidential debate — and they convinced her that a second Trump presidency would be a grave threat to her home of Poland and the larger region.

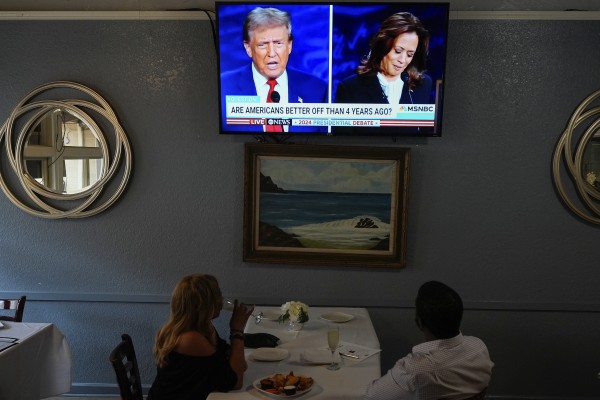

Former President Donald Trump twice refused to directly answer a question during the debate about whether he wanted U.S. ally Ukraine to win the war. Meanwhile, Vice President Kamala Harris praised American and NATO support for Ukraine in its fight against Russia's invasion so far — and called for it to continue.

“Otherwise, (Russian President Vladimir) Putin would be sitting in Kyiv with his eyes on the rest of Europe. Starting with Poland,” she said. “And why don’t you tell the 800,000 Polish Americans right here in Pennsylvania how quickly you would give up for the sake of favor and what you think is a friendship with what is known to be a dictator who would eat you for lunch?”

Harris’ emphasis on the need to stand up to Putin resonated Wednesday in Poland, a nation of 38 million people whose geography makes it particularly sensitive to the debate. The NATO member is wedged between its European Union partners to the west and, to the east, the Russian region of Kaliningrad, Russian ally Belarus and Ukraine.

As a result, the war is always present in Poland, whether from occasional accidental incursions into Polish airspace or the large numbers of refugees who have settled there.

Fears that Putin could prevail in Ukraine and then turn his sights on areas of Europe once under Moscow's control — including the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia — have been present since Russia first illegally annexed Crimea in 2014. They have grown more acute following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, particularly at times when Russia has had the momentum on the battlefield.

If Ukraine loses, Putin “will take further steps,” said Kwiatkowska, a 75-year-old resident of Warsaw whose Ukrainian mother and Polish father met after World War II.

She was particularly dismissive of Trump’s claim in Tuesday night’s debate that he could easily end the war. “I will get it settled before I even become president,” Trump said.

“Just empty words,” she scoffed, as she did her morning shopping in Warsaw, a capital that, like cities in Ukraine today, was bombed to near destruction during World War II.

Sławomir Dębski, a professor of strategy and international affairs at the College of Europe in Natolin, also found it “far-fetched” for Trump to claim he could force Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to the negotiating table before he even entered the White House.

“There’s little reason to believe Putin would agree to such a meeting unless Ukraine were prepared to capitulate, which would be unlikely,” Dębski said. In fact, Putin earlier this year insisted Ukraine must give up vast amounts of territory and avoid joining NATO simply as a condition to start negotiations.

Dębski contended that it was a “clear mistake” on Trump's part not to say outright that he wants Ukraine to win the war. But he also argued that the Biden administration has made a mistake because it “committed itself to help Ukraine as long as it takes, but refused to state that it should mean Ukraine’s victory."

When Trump first won the presidency, there was strong enthusiasm for him in Poland, from the government and public. The conservative authorities in power at the time shared many of his positions, particularly in their opposition to migration. Poland, one of the largest spenders of defense among NATO allies, also welcomed his push that other allies pay more on defense themselves.

Today's government of Prime Minister Donald Tusk has made its critical views of Trump known. And with the brutal war in Ukraine, many Poles have soured on the former president, who has a history of admiring comments about Putin.

Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov dismissed the back-and-forth in the debate, saying Putin’s name is used as “one of the tools in the domestic political struggle of the United States.”

But the debate was a top news item in Poland on Wednesday, where the media praised Harris' performance. Journalist Jacek Nizinkiewicz called the debate “a very strong and unambiguous signal for Ukraine and Polish security” in a opinion piece in a leading newspaper, Rzeczpospolita.

Back in Pennsylvania, a crucial swing state, some of the Americans of Polish descent whom Harris sought to reach were also mulling the debate.

At Lucky’s Kielbasi Shop in Shenandoah — in a region whose coal mines drew waves of Polish immigrants more than a century ago -- opinion was split.

“I didn’t like what she said. I don’t think that’s true,” said Cecilia Heffron, 82, who supports Trump. “I know if Trump gets in, we wouldn’t have a war.”

But her friend Lorraine McDonald, a Harris supporter, said the vice president's statement got her attention and she believes Putin would invade Poland if given the chance.

“If Putin gets a hold of Ukraine, and it’s OK, he’s going for the rest. ... He’s not going to stop there,” she said.

In Warsaw, Andrzej Nowak, 67, offered the same analysis.

“It’s important for Poland that Ukraine wins," Nowak said. “Because there is no telling what this madman will come up with.”

___

Associated Press writer Michael Rubinkam contributed from Shenandoah, Pennsylvania.

http://accesswdun.com/article/2024/9/1262140