MEDFORD, Mass. (AP) — Flerentin “Flex” Jean-Baptiste missed so much school he had to repeat his freshman year at Medford High outside Boston. At school, “you do the same thing every day,” said Jean-Baptiste, who was absent 30 days his first year. “That gets very frustrating.”

Then his principal did something nearly unheard of: She let students play organized sports during lunch — if they attended all their classes. In other words, she offered high schoolers recess.

“It gave me something to look forward to,” said Jean-Baptiste, 16. The following year, he cut his absences in half. Schoolwide, the share of chronically absent students declined from 35% in March 2023 to 23% in March 2024 — one of the steepest declines among Massachusetts high schools.

Years after COVID-19 upended American schooling, nearly every state is still struggling with attendance, according to data collected by The Associated Press and Stanford University economist Thomas Dee.

Roughly one in four students in the 2022-23 school year remained chronically absent, meaning they missed at least 10% of the school year. That represents about 12 million children in the 42 states and Washington, D.C., where data is available.

Before the pandemic, only 15% of students missed that much school.

Society may have largely moved on from COVID, but schools say they're still battling the effects of pandemic school closures. After as much as a year at home, school for many kids has felt overwhelming, boring or socially stressful. More than ever, kids and parents are deciding it's OK to stay home, which makes catching up even harder.

In all but one state, Arkansas, absence rates remain higher than they were pre-pandemic. Still, the problem appears to have passed its peak; almost every state saw absenteeism improve at least slightly from 2021-22 to 2022-23.

Schools are working to identify students with slipping attendance, then providing help. They're working to close communication gaps with parents, who often aren't aware their child is missing so much school or why it's problematic.

So far, the solutions that appear to be helping are simple — like postcards to parents that compare a child's attendance with peers. But to make more progress, experts say, schools must get creative to address their students' needs.

Across district and charter schools in Oakland, California, chronic absenteeism skyrocketed from 29% pre-pandemic to 53% in 2022-23. The district asked students what would convince them to come to class.

Money, they replied, and a mentor.

A grant-funded program launched in spring 2023 paid 45 students $50 weekly for perfect attendance. Students also checked in daily with an assigned adult and completed weekly mental health assessments.

Paying students isn't a permanent or sustainable fix, said Zaia Vera, the district's head of social-emotional learning.

But many absent students lacked stable housing or were helping to support their families. “The money is the hook that got them in the door," Vera said.

More than 60% improved their attendance after taking part, Vera said. The program is expected to continue, along with district-wide efforts aimed at creating a sense of belonging. Oakland's African American Male Achievement project, for example, pairs Black students with Black teachers who offer support.

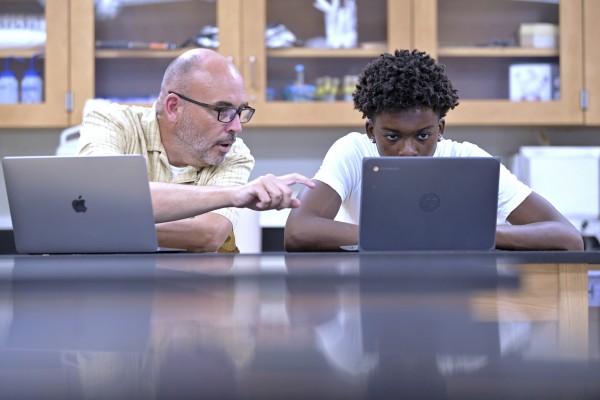

Kids who identify with their educators are more likely to attend school, said Michael Gottfried, a University of Pennsylvania professor. According to one study led by Gottfried, California students felt “it’s important for me to see someone who’s like me early on, first thing in the day,” he said.

A caring teacher made a difference for Golden Tachiquin, 18, who graduated from Oakland’s Skyline High School this spring. When she started 10th grade after a remote freshman year, she felt lost and anxious. She later realized these feelings caused the nausea and dizziness that kept her home sick. She was absent at least 25 days that year.

But she bonded with an Afro-Latina teacher who understood her culturally and made Tachiquin, a straight-A student, feel her poor attendance didn’t define her.

“I didn’t dread going to her class,” Tachiquin said.

Another teacher had the opposite effect. “She would say, ‘Wow, guess who decided to come today?’ ” Tachiquin recalled. “I started skipping her class even more.”

In Massachusetts, Medford High School requires administrators to greet and talk with students each morning, especially those with a history of missing school.

But the lunchtime gym sessions have been the biggest driver of improved attendance, Principal Marta Cabral said. High schoolers need freedom and an opportunity to move their bodies, she said. “They’re here for seven hours a day. They should have a little fun.”

Chronically absent students are at higher risk of illiteracy and eventually dropping out. They also miss the meals, counseling and socialization provided at school.

Many of the reasons kids missed school early in the pandemic are still firmly in place: financial hardship, transportation problems, mild illness and mental health struggles.

In Alaska, 45% of students missed significant school last year. In Amy Lloyd’s high school classes in Juneau, some families now treat attendance as optional. Last term, several of her English students missed school for vacations.

“I don’t really know how to reset the expectation that was crushed when we sat in front of the computer,” Lloyd said.

Emotional and behavioral problems also have kept kids home from school. Research shared exclusively with AP found absenteeism and poor mental health are “interconnected,” said University of Southern California professor Morgan Polikoff.

For example, in the USC study, almost a quarter of chronically absent kids had high levels of emotional or behavioral problems, according to a parent questionnaire, compared with just 7% of kids with good attendance. Emotional symptoms among teen girls were especially linked with missing lots of school.

When chronic absence surged to around 50% in Fresno, California, officials realized they had to remedy pandemic-era mindsets about keeping kids home sick.

“Unless your student has a fever or threw up in the last 24 hours, you are coming to school. That’s what we want,” said Abigail Arii, director of student support services.

Often, said Noreida Perez, who oversees attendance, parents aren’t aware physical symptoms can point to mental health struggles – such as when a child doesn’t feel up to leaving their bedroom.

More than a dozen states now let students take mental health days as excused absences. But staying home can become a vicious cycle, said Hedy Chang, of Attendance Works, which works with schools on absenteeism.

“If you continue to stay home from school, you feel more disengaged,” she said. “You get farther behind.”

Changing the culture around sick days is only part of the problem.

At Fresno’s Fort Miller Middle School, where half the students were chronically absent, two reasons kept coming up: dirty laundry and no transportation. The school bought a washer and dryer for families' use, along with a Chevy Suburban to pick up students who missed the bus. Overall, Fresno’s chronic absenteeism improved to 35% in 2022-23.

Melinda Gonzalez, 14, missed the school bus about once a week and would call for rides in the Suburban.

“I don’t have a car; my parents couldn’t drive me to school,” Gonzalez said. “Getting that ride made a big difference.”

___

Becky Bohrer contributed reporting from Juneau, Alaska.

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

http://accesswdun.com/article/2024/8/1257619