There are a variety of reasons that a race track may close. Sometimes it’s due to economic situations, sometimes due to a lack of interest or perhaps due to encroaching residential areas.

In northeast Georgia, one famous raceway met a watery fate.

In Gainesville, Georgia, there lays a raceway under the waters of Lake Lanier. In Laurel Park, under the waters of the lake, sits the Gainesville Speedway – sometimes referred to as the Looper’s Speedway. Occasionally, when the lake is low, the top of the large concrete grandstands that once held capacity crowds to watch the racing heroes of the day.

But otherwise, there’s no sign that a raceway once sat there.

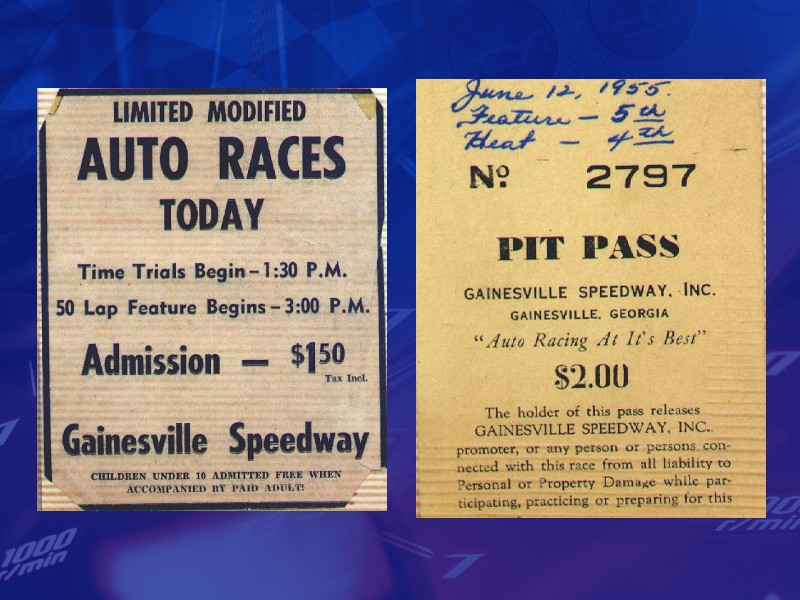

The track was built in 1948, just off of US Highway 129. And it came about as many things in racing have – due to an argument.

Gainesville residents Max Looper and Frank Pirkle, along with Georgia Racing Hall of Fame driver Gober Sosebee of Dawsonville, Georgia, had leased the horse track at Gainesville’s, North East Georgia Fairgrounds for a race in 1947. The race was such a success, that the trio wanted to run another event. However, the fair board would not clear them for another date.

Incensed, Looper decided to build his own track.

The speedway was actually incorporated in nearby Dawson County, according to the charter records, operating as “Looper’s Speedway Incorporated.” The charter was granted on December 20, 1947.

Looper oversaw construction of the half-mile, semi-banked oval through the first part of 1948. Pirkle, the owner of the Pirkle Tire Company and other businesses in Gainesville, was in charge of admission and concessions, while Sosebee organized the drivers to compete.

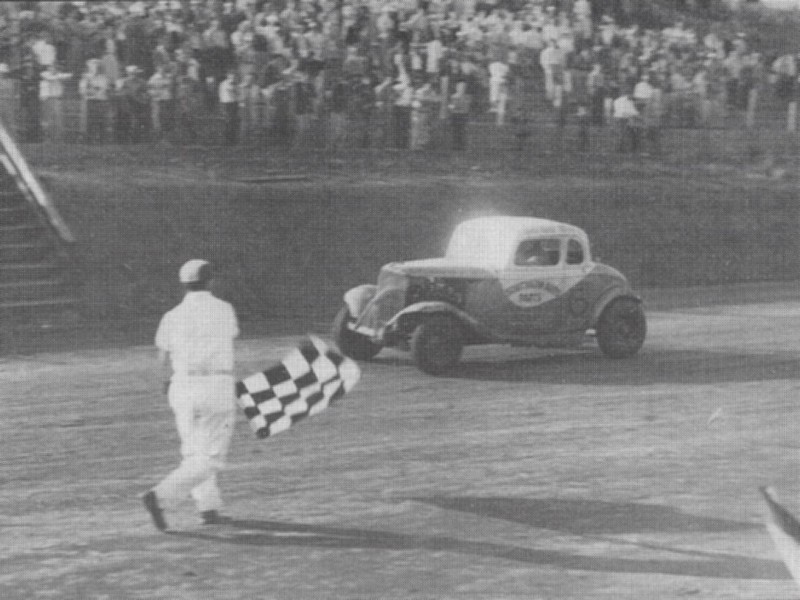

Looper’s Speedway opened in August of that year, with Sosebee scoring the win. It would operate for the next two years under Looper’s direction, with drivers coming from all over the state to compete.

Gainesville native Bobbie Whitmire competed in his second ever race at the speedway in 1949.

“It was a good, fast track,” Whitmire said. “We didn’t have a dust problem there. It was laid out really good.”

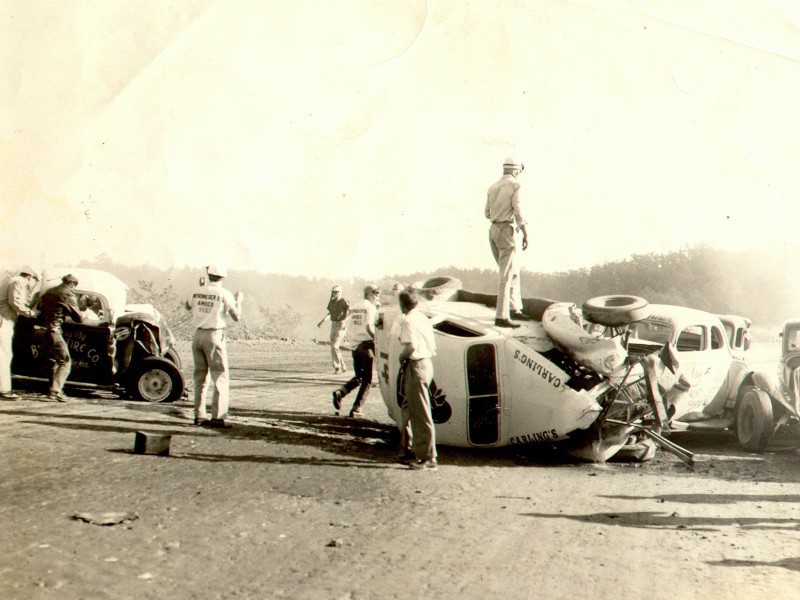

Like many tracks of the day, while there was a bank in front of the grandstands to protect the fans, the track had no guardrails or walls around the turns or down the backstretch. That made off-track excursions an adventure.

“We went to the corn patch, or down the bank,” Whitmire said. “I loved the track. I always considered it one of my favorites.”

Whitmire was witness to a very special piece of racing history at the speedway in 1949, when pioneer female racer Sara Christian of Dahlonega, Georgia dominated the day.

Christian, recognized now as one of the pioneer drivers in NASCAR’s early days, swept the card at the track, winning the pole, her heat race and the feature over a field of top male drivers including Gober Sosebee and Chester Barron.

“I ended up qualifying third, Sara qualified on the pole,” Whitmire said. “I was running right up front behind her (at one point). I saw enough of her driving in the feature, and I could tell that woman knew how to drive a car.”

That same year, Christian would compete in the first NASCAR Cup Series race in Charlotte, North Carolina. She would become the first woman to score a top ten finish in a NASCAR Cup Series race at Langhorne Speedway in Langhorne, Pennsylvania. Later that year, she finished fifth at Heidelberg Raceway near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in what remains the best finish in NASCAR Cup Series history for a female driver.

She would be named United States Drivers Association Woman Driver of the Year in 1949. In 2004, she was inducted into the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame.

After the 1949 season, Looper would give up the speedway at the behest of his family, and it sat dormant for the 1950 and 1951 seasons.

The speedway reopened in 1952, under the ownership of George DeLong, John Caviness and Doc Stowe as the Gainesville Speedway.

Under the new direction, a Gainesville firm replaced the old wooden grandstands with modern, concrete stands, featuring a tapered seat for more comfort for the fans.

While the track was not NASCAR sanctioned, it drew the top drivers of the day. Several members of the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame competed there, including NASCAR Hall of Famer Tim Flock and his brothers Bob, and Fonty – who would make the trip to Gainesville not following the NASCAR tour. Gober Sosebee continued to race there, along with fellow GRHOF members Jack Smith, Charley Mincey, Billy Carden, Ed Samples, Gainesville’s Bud Lunsford and others.

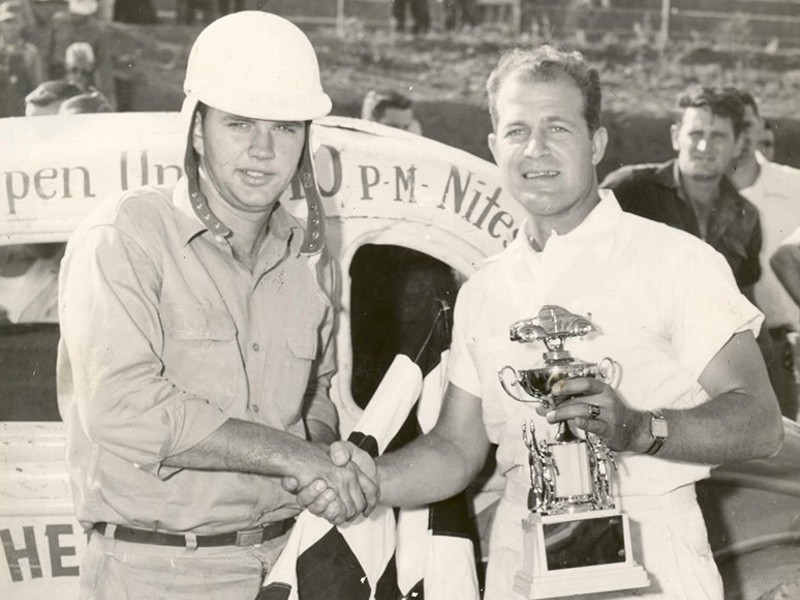

One of the most popular stories from the Gainesville Speedway came from a now NASCAR Hall of Fame member – though no one knew it at the time.

“Everybody came to the track one Sunday to race and a Cadillac was park on the grounds with the driver asleep inside,” said racing historian Mike Bell. “It towed a raggedy old Ford coupe that had wooden bumpers, and everybody laughed.”

The laughter stopped when the driver – legendary stock car ace Curtis Turner – set fast time, won his heat and drove away from all competition in the feature. All of this on a day when he wasn’t even slated to race there.

As the story goes, Turner was on his way to a race somewhere south when he became tired during his overnight drive. He spotted a sign for the Gainesville Speedway, and followed them right to the track. After catching a few hours sleep in his car, he got out, washed his face and then dusted the competition.

“He left them in his dust,” Bell said.

Over the coming years, Turner’s legend would grow, and he became one of the biggest folk heroes in southern stock car racing. He would lose his life in a private airplane crash in 1970. He was inducted into the NASCAR Hall of Fame in 2016.

Over the next few years, Gainesville Speedway continued to draw in the best of the best race drivers from around the southeast.

“Ever driver that ran stock cars in North Georgia in the fifties ran there,” Bell said. “They came from Canton and Jasper to Toccoa, from Winder and Athens to the Carolinas and beyond.”

In addition to the oval track, the owners gave straight line racing a shot, as they build a dirt drag strip on the property in 1956.

“Bobbie (Whitmire) says it ran from the starting line near the lake’s edge where the grandstands are towards what was then US Highway 129,” Bell said. “It ran in 1956 and there was talk of continuing it after the lake came up but the property probably got sold for the park.”

Despite the success of the track, there was a deluge on the horizon.

The project for Buford Dam was already being studied when Max Looper bought the project. Funded by the Federal Government, the building of the dam began in 1950. The dam was completed in 1956, and the lake began filling in.

The speedway was right in the path of the rising waters, and was eventually condemned after being deemed as being too close to the shoreline.

The track got a short reprieve after cities downstream from the dam complained because they got their water from the river. That led engineers to fill the lake slowly to keep from shorting the towns on water.

The last race at the Gainesville Speedway was held in the fall of 1956. It was a 100-lap Southern Racing Enterprises Late Model feature won by Georgia Racing Hall of Famer Roscoe Thompson.

A few months later, the track was buried under the waters of Lake Lanier. Oddly enough, nothing was demolished at the track. The scoring tower and concession stand was left intact as the land flooded.

Occasionally, during the summer months, the lake level will get low enough that the top few rows of the concrete grandstands can be seen. During the drought of 2007, several of those seats were seen for the first time since they went under.

Laurel Park is one of the most popular fishing spots on the lake now. Maybe it’s fitting that the area where race fans would gather to watch their favorites over 70 years ago can still bring people in – although it’s for an altogether slower- and quieter – sport.

http://accesswdun.com/article/2020/3/889224/gainesville-speedway-buried-underwater-but-memories-remain