They are well aware that there are few faster ways for a candidate to get into political trouble than to wade into the sensitive subject of the water shortages afflicting large areas of the nation. That's especially true when it comes to proposals for regional water sharing. Water-rich regions such as the Great Lakes states have long been wary that water-scarce, but politically robust regions like the Sun Belt will try to siphon off their precious resource.

Such competing regional interests are laden with political implications. The handful of states leading off the presidential nominating contests in January tentatively includes the Great Lakes state of Michigan, as well as Nevada in the desert Southwest and South Carolina and Florida in the Southeast, which is suffering a historic drought.

Several Great Lakes states, including Ohio, are also swing states certain to be top priorities in the general election.

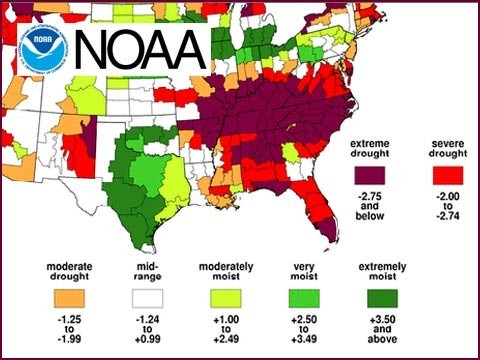

Yet sidestepping the problem is a luxury that presidential candidates won't have forever, Duke University political scientist David Rohde said. Population is surging in the arid West, where water shortages are chronic, and in the Southeast, where the drought has prompted spats between neighboring states.

The government projects that at least 36 states will face water shortages within five years because of rising temperatures and evaporation rates, lack of rain, urban sprawl, waste and overuse.

Water levels of the three biggest Great Lakes - Superior, Huron and Michigan - have been in steep decline since the late 1990s. The region's eight state legislatures are considering a compact that would prohibit sending water outside the drainage basin except to localities that straddle the boundary.

A group representing the governors of the eight Great Lakes states urged the presidential contenders last week to endorse a wide-ranging plan for protecting the lakes - including keeping them off-limits to outsiders.

"It's too bad Iowa isn't a Great Lakes state, because if it were, we'd have all kinds of positions (from the candidates)," said Wisconsin Gov. Jim Doyle, the group's chairman. The Iowa caucuses are Jan. 3.

The Associated Press asked the leading Democratic and Republican presidential candidates a series of written questions about water policy, including whether regions that have relatively plentiful supplies, such as the Great Lakes, should share with those running short.

Campaign officials for Republicans Rudy Giuliani and Fred Thompson and Democrat John Edwards declined comment or didn't answer.

Only Hillary Rodham Clinton, the Democratic front-runner, responded at length, saying she opposes diverting water from the Great Lakes, "one of our most precious natural resources." The lakes compose about 90 percent of the nation's fresh surface water and nearly 20 percent of the world supply.

"I would not overrule a state's lawful right to protect its water supplies," Clinton said in an e-mail. She also advocated techniques to stretch water supplies.

Republicans John McCain and Mitt Romney responded to reporters' questions at recent campaign stops in Michigan.

McCain, an Arizona senator, said the federal government should not require diversion of Great Lakes water, and the Southwest should focus on ways to conserve while building new storage projects.

Romney would not comment specifically on the Great Lakes, but said a water sharing agreement reached this year among seven Western states dependent on the Colorado River set a good example for others.

Democrat Barack Obama said in an e-mail that the federal government "needs to be a fair dealer between competing water consumers" and should "create a national plan to help communities adopt water use policies that better conserve water."

Democrat Bill Richardson, the governor of New Mexico, has been one of the few candidates to raise the issue with voters.

In a recent interview with the Las Vegas Sun, Richardson called for a national water policy and observed that "Wisconsin is awash in water," which many in the lakes region interpreted as a threat to grab their treasure.

Suddenly, Richardson was a whipping boy on editorial pages, Internet message boards and talk shows from Minnesota to New York.

Questioned by reporters in Detroit, Richardson insisted he had never suggested piping Great Lakes water elsewhere and that he was calling for states to swap ideas, not their water.

Great Lakes water sharing has been a political minefield before. During the 2004 campaign, Democrat John Kerry said the matter would require a "delicate balancing act" between states' rights and national needs.

A spokesman insisted Kerry opposed diverting Great Lakes water, but an uproar ensued anyway.

"Whatever the candidates say about it is likely to alienate somebody," said Rohde, the politician scientist. "So their judgment so far seems to be not to say anything."

Georgia Drought

http://accesswdun.com/article/2007/11/203962